Arts and Crafts movement

Formed in England in the mid-19th century, this movement emulated a goal of Berlin’s World Heritage housing estates: to focus on high-quality design in handmade products, rather than produce soulless, mass-market wares of industrialisation. Members took particular care to ensure that the workmanship suited the material and traditional crafts. Forms were to be simple but interesting. Some Arts and Crafts ideals were adopted by the craftsmen’s association Deutscher Werkbund, by proponents of reformed housing and from 1907, by the Bauhaus design school. However, they increasingly came into conflict with Functionalism, another design ideal that was oriented more towards high utility value and mass production. For Berlin’s World Heritage housing estates, a compromise was sought between low-cost type construction and individual design with intriguing details and materials.

Association “The Ring”

The Siemensstadt Large Housing Estate is often referred to as the “Ring Estate”. All of its designing architects were members of The Ring, an association founded in 1926 that consisted of 20-odd architects from around Germany. Two years before, the group was founded as “The Ring of Ten” with as many Berlin architects, but its members decided to expand the group to include colleagues working outside Berlin. The common goal was the New Building style and a fresh design vocabulary, as is obvious on the Siemensstadt estate despite the different personal styles of its members. A counter-movement to The Ring called “The Block” eventually emerged, made up of conservatives and traditionalists whose positions were similarly unshakable.

Balcony access homes

The term refers to a type of housing block not very common in Germany, where a series of rental apartments is accessible from a balcony open to one side and running across the front of the building. This simple idea cut building costs by moving the staircase and apartment doors outside, a familiar feature of American motels. The walkway is shared by all tenants on that floor, usually with a guard railing and leading to an open staircase at the side of the house. A similar example is Otto-Rudolf Salvisberg’s bridge house at the White City estate in Berlin-Reinickendorf, and at the south-east end of the Siemensstadt estate in Hans Scharoun’s extension from the 1950s.

Barrier-free access

Accessibility for the physically or mentally handicapped means easy, barrier-free entry to buildings, cultural sites and sources of information – a familiar demand today. In architecture, a building should not only have barrier-free access to stairs, but also wheelchair access via shallow ramps or elevators. This may cause conflicts with monument conservation authorities, who insist that a monument should be preserved as faithfully as possible. Still, there is usually leeway for local solutions at a particular monument, such as the Schillerpark Estate.

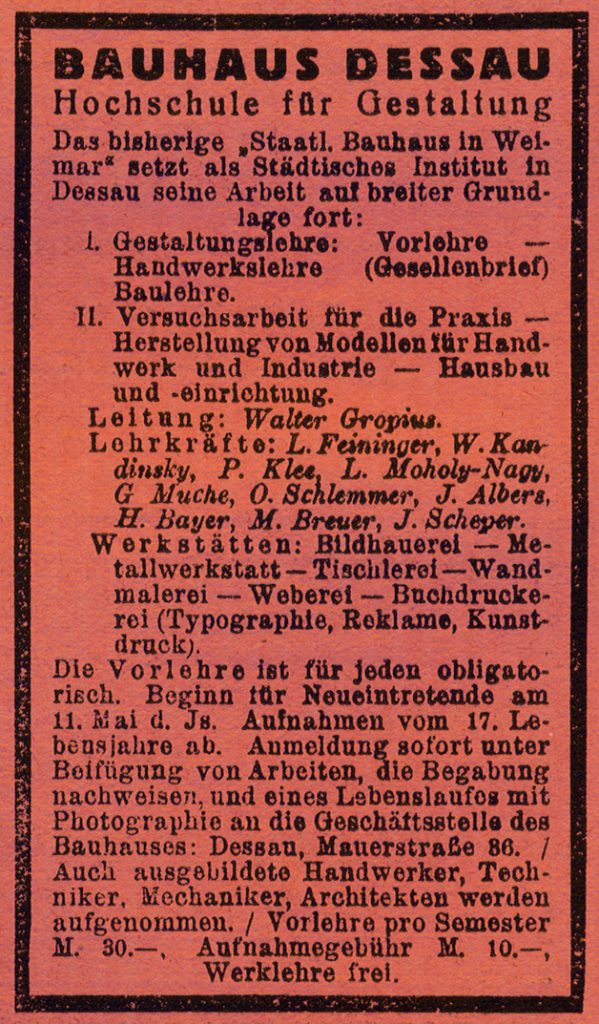

Bauhaus > design school

The Bauhaus is considered the most famous and influential design school of the 20th century. Its aim was to bring together art, crafts and industry and to comprehensively reform design education. Based on the teaching of design fundamentals, materials science and free experimentation in individual workshops, new forms were to be created that could be easily manufactured in increasingly industrial processes. This idea was already partly embraced by other movements such as the Deutscher Werkbund craftsmen’s association. However, the educational concept at the Bauhaus would be the first to set a global standard.

Locations, goals and history

The Bauhaus was founded in 1919 by the architect Walter Gropius. As director until 1928, he would essentially determine the school’s direction and overall destiny. The Bauhaus was initially located in the city of Weimar, about 300 kilometres (186 miles) south-west of Berlin. The Bauhaus set itself up at the Weimar School of Applied Arts founded in 1907 by architect Henry van de Velde in 1907, whose program was incorporated into the new Bauhaus curricula. In 1925, the school moved to nearby Dessau, where the teaching and workshop facilities were more clearly oriented towards industrial production. In Dessau, the school moved into a spectacular, newly designed complex that embodied the maxims of the New Building movement. In 1928, Hannes Meyer took over as director, and with his socio-political slogan “Needs of the people over the needs of luxury”, the Bauhaus focussed even more on Functionalism as a design principle and promoted cost-effective mass production. The National Socialists, however, did not take kindly to this development. They saw the Bauhaus as a left-wing hotbed of new talent and strongly disapproved of its modern forms. Under the next director, architect Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, the Bauhaus moved to Berlin in 1932 and operated as a purely private institution. Nevertheless, the school was forced to dissolve in 1933 due to ongoing reprisals by the Nazis.

Post-war period and significance today

The great influence of the Bauhaus school is undisputed. Divided into preliminary courses and master classes, its curricula would later serve as a template for modern design education. New disciplines such as graphic, textile and industrial design originated here. Many former masters such as Marcel Breuer and Walter Gropius emigrated to the United States in the 1930s and taught at the renowned Harvard University in Boston. The Bauhaus teachings continued in the New Bauhaus school founded in Chicago, under the direction of former Bauhaus master László Moholy-Nagy. In Germany, an attempt was made in the early 1950s to tie in with the original Bauhaus curricula by founding the Ulm School of Design. Today, the special significance of the Bauhaus is reflected not least in the widespread use of the term “Bauhaus style”. However, its broad use is controversial, since there were many other important reform and avant-garde movements before and during the Bauhaus era. For example, Berlin’s World Heritage housing estates are not Bauhaus architecture in the strict sense, but do show some parallels.

Bauhaus > masters

At the Bauhaus school of design, many prominent artists, architects and designers were appointed Meister (masters). These included such illustrious names as Paul Klee, Lionel Feininger, Wassily Kandinsky, Oskar Schlemmer and Johannes Itten, whose works can still be seen in many museums and collections of Classical Modernism. With their life-reforming ideas and artistically abstract works, these masters shaped the early Bauhaus spirit in Weimar. Above all, the charismatic Johannes Itten played a special role. He was a follower of the exotic-esoteric Mazdaznan doctrine, which combined elements from various religious traditions. These traditions included vegetarian food as well as breathing and meditation exercises.

The Bauhaus quickly became as famous for its free thinking and unusual design as for its notoriously lively festivities. All this frightened the bourgeois-conservative community and increasingly led disgruntled Weimar residents to reject the Bauhaus. From around 1923, the school’s teachings shifted sharply towards industrial and rational design, which many critics regarded as cold and technocratic. In 1925, the Bauhaus moved its headquarters from sleepy Weimar to neighbouring Dessau, an up-and-coming industrial hub. In 1929, the Hungarian-born multimedia designer László Moholy-Nagy was appointed as a new master to succeed Itten. Other personalities such as Marianne Brandt, Lilly Reich and Gunta Stölzl as well as Josef Albers, Herbert Bayer, Marcel Breuer, Mart Stam, Gerhard Marcks, Adolf Meyer and Walter Peterhans were entrusted with individual workshops. Although the school was otherwise considered quite progressive, women were underrepresented among the masters.

Through various initiatives, some Bauhaus members maintained close contact with the architects of the World Heritage estates, including those in the craftsmen’s association Deutscher Werkbund, the architects’ association The Ring, and the Gläserne Kette group of letter-writers initiated by Bruno Taut.

Berlin > Elektropolis

From the mid-19th century onwards, the Berlin region developed into an international hub of the power and electrical industries. During industrialisation, large power plants, industrial facilities, factories and many other businesses sprang up in the city and its outskirts. These structures and the new residential quarters around them shaped entire areas and city districts, such as the industrial zone near Siemensstadt and the district of Oberschöneweide. Apart from the electrical industry, there were several large companies that hired large numbers of workers and spurred the city’s population growth.

At the turn of the 20th century, many big German companies were based in Berlin and its environs. These included engineering concern Siemens, the Borsig machine works, electrical plant supplier AEG, chemicals manufacturer Schering (now part of Bayer), lighting manufacturer Osram and pioneers of consumer electronics such as Telefunken and Blaupunkt. Because of the concentration of companies in the power and electrical sectors, the name “Elektropolis” was coined (“polis” is the Greek word for city). This development coincided with the expansion of early public transport. In 1881, the first electrically powered railway went into operation in the Lichterfelde district. Alexanderplatz and Potsdamer Platz became busy transfer stations for public transport and major traffic junctions. In 1920, after the merger of districts and towns that formed Greater Berlin, the metropolis was the largest industrial city in Europe.

Berlin > Greater Berlin

Industrialisation created a huge number of new jobs in factories around Berlin, triggering a dramatic rise in the population. After 1850, the population of the region doubled approximately every 25 years. However, Berlin’s leap to a cohesive metropolis occurred only after Greater Berlin was founded in 1920. Seven neighbouring towns (Spandau, Köpenick, Charlottenburg, Wilmersdorf, Schöneberg, Neukölln and Lichtenberg), as well as 59 rural communities and 27 estate districts, were incorporated under a single administration. On 25 April 1920, the Prussian State Assembly narrowly voted to approve the merger by 164 to 148. Prosperous towns such as Charlottenburg and Wilmersdorf feared for their economies, but the merger was definitely good for housing construction. Vast land reserves were tapped for building projects, and the new districts gave Berlin several independent centres with their own working infrastructures.

Berlin > House interest tax

Berlin’s house interest tax was introduced in 1924, four years after the grand merger of communities that created Greater Berlin. The inspiration for the tax, however, went back 20 years earlier. The cash-strapped Berlin government adapted the earlier proposals of Martin Wagner, the city’s chief building planner, to create a way of generating income from new housing developments. Thanks to this new levy, private landlords, who largely escaped the steep currency devaluation of the early 1920s, suddenly found themselves drawn into the financing of public housing. Politicians agreed to invest a fixed part of this tax revenue in public housing and to control the outcome, thresholds of quality and eligibility were set. This policy was welcomed especially by Berlin’s left-wing parties, as it helped to stem the widening income gap between rich and poor.

Two things were instrumental in the policy results. First, housing construction in the late 19th century lay almost entirely in the hands of wealthy landowners and investors. Second, construction and property were an extremely secure investment in times of inflation. As inflation surged between 1914 and 1924, property values remained stable compared to cash and savings deposits, which rapidly lost purchasing power. At the same time, the dwindling value of cash quickly became a problem when rent was due. Since property ownership in big cities like Berlin was primarily the domain of the wealthy, the divide between the rich and poor widened rapidly. As a result, house and land ownership is today still considered a safe investment and is often referred to as “concrete money”.

The house interest tax only bore fruit after the introduction of new housing companies and new quality standards for residential developments to be subsidised by the tax. Only “good” projects would qualify, to be determined by the state in advance. Proceeds of the house interest tax only went into construction projects that met predefined terms for apartment sizes and floor plans.

Berlin > Housing shortage

Berlin suffered a chronic lack of housing at the beginning of the 20th century, caused by the consequences of the First World War, a deprived post-war economy and ongoing migration from the countryside to the city. Conditions were often dire, especially in the workers’ districts. A single room in an apartment was only considered overcrowded when it had five occupants. Larger apartments were often shared by several families. Cellars and attics doubled as living space and were rented out. Home-based work was not uncommon, as children or elderly grandparents helped to raise money for rent and food.

At the time, the bulk of Berlin residents lived in tenement blocks, especially in the workers’ districts. These blocks became more crowded as layers of wings and inner courtyards were added one by one. The hygiene for common tenants is difficult to imagine today: around 1920, nine out of ten apartments did not have private bathrooms, as toilets in the courtyards or stairwells were shared by several families and residents. Heating came from stoves, as central heating was unheard of in these simple quarters. For the very poor, special living arrangements were adopted for “sleepers” or “dry dwellers”.

Berlin > municipal parliament

Called Stadtverordnetenversammlung in German, this was the name given to Berlin’s municipal parliament founded in 1809 and the forerunner of today’s state House of Representatives. The construction of Berlin’s major housing estates during the Weimar Republic was sealed in its chambers. Among the left-leaning parties in the assembly were the Social Democratic Party of Germany (SPD), the Independent Social Democratic Party of Germany (USPD) and the Communist Party of Germany (KPD). During the Weimar Republic, these parties formed the political left wing (placed on that side of parliament, as the seating plan indicated), and faced a growing number of bourgeois-conservative parties on the right. Among the right-wing parties were representatives of the now-defunct Catholic Centre Party (formerly DZP), the national-conservative German National People’s Party (DNVP), the moderate German Democratic Party (DDP), the national-liberal German People’s Party (DVP) and from 1929, Hitler’s National Socialist German Workers’ Party (NSDAP), which rapidly gained in popularity. Other smaller bourgeois and right-wing parties included the Reich Party of the German Middle Class (WP), the German Socialist Party (DSP) and the Christian Social People’s Service (CVD).

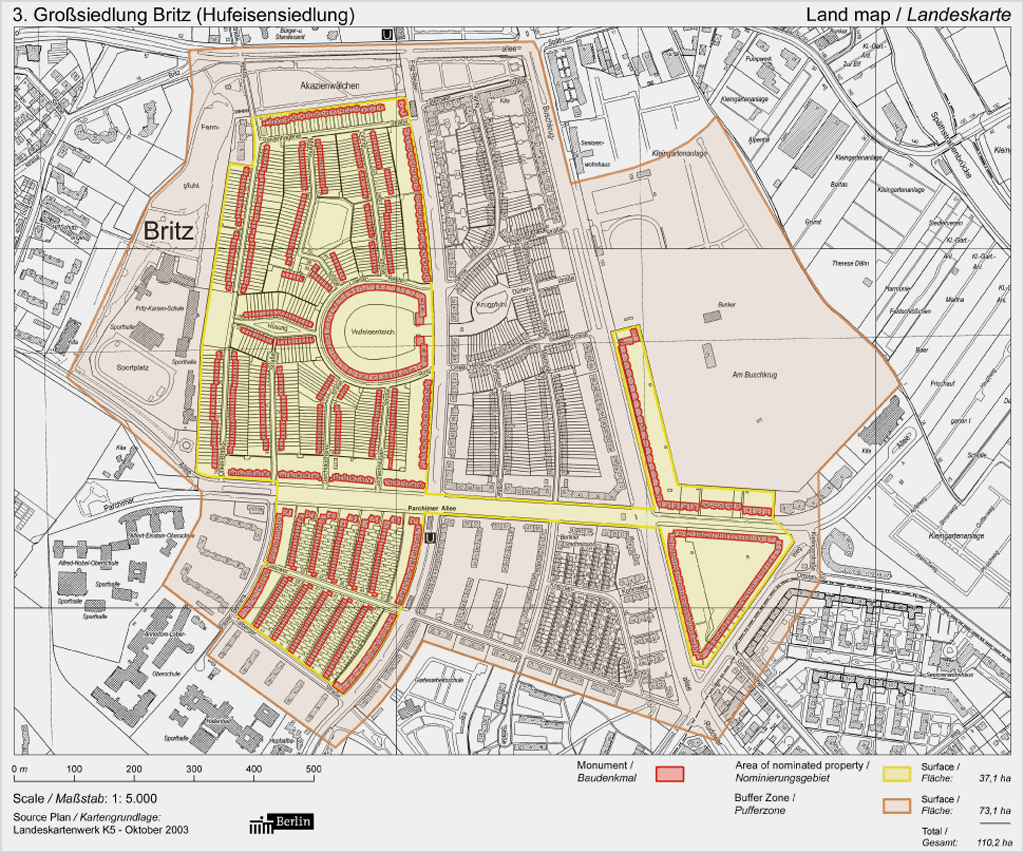

Buffer zone

New buildings or conversions located near an outstanding monument or UNESCO World Heritage Site are subject to special requirements. This is why World Heritage has clearly defined so-called buffer zones, which are designed to prevent the appearance and overall impact of these sites from being undermined. An example would be a new high-rise building that obstructs the view of an important historical tower or church. The city of Dresden shows that such scenarios are not just theory. Dresden was stripped of its UNESCO World Heritage status because a new bridge obstructed the view of its unique skyline. Similar discussions took place about Cologne’s plans to erect buildings that would have obscured the view of Cologne Cathedral, a World Heritage Site.

Berlin’s World Heritage housing estates are girded by a buffer zone that we have marked in bright pink on our interactive tour maps. The actual World Heritage areas of the estates are highlighted in yellow within the buffer zones. This colour scheme matches the one used in the official maps published by the city administration (see example below).

Cooperatives > 1892 eG

This is the common abbreviation of Berliner Bau- und Wohnungsgenossenschaft von 1892 eG, a registered housing cooperative founded as the savings and building society Berliner Spar- und Bauverein in 1892. Its goal was to provide inexpensive living space for its members, who acquired shares in the cooperative. These shares became savings deposits with which new buildings could be financed, and in return, the members acquired residential rights that were weighted according to their deposits. Today, two of the city’s World Heritage housing estates – Falkenberg Garden City and the Schillerpark Estate – are still owned by the cooperative. The “1892”, as it is commonly known, has over 14,000 members and a portfolio of almost 7,000 apartments. In recent years, new buildings sprang up near these estates and adopted elements of their famous neighbours, thus blending in with the surrounds.

Cooperatives > definition

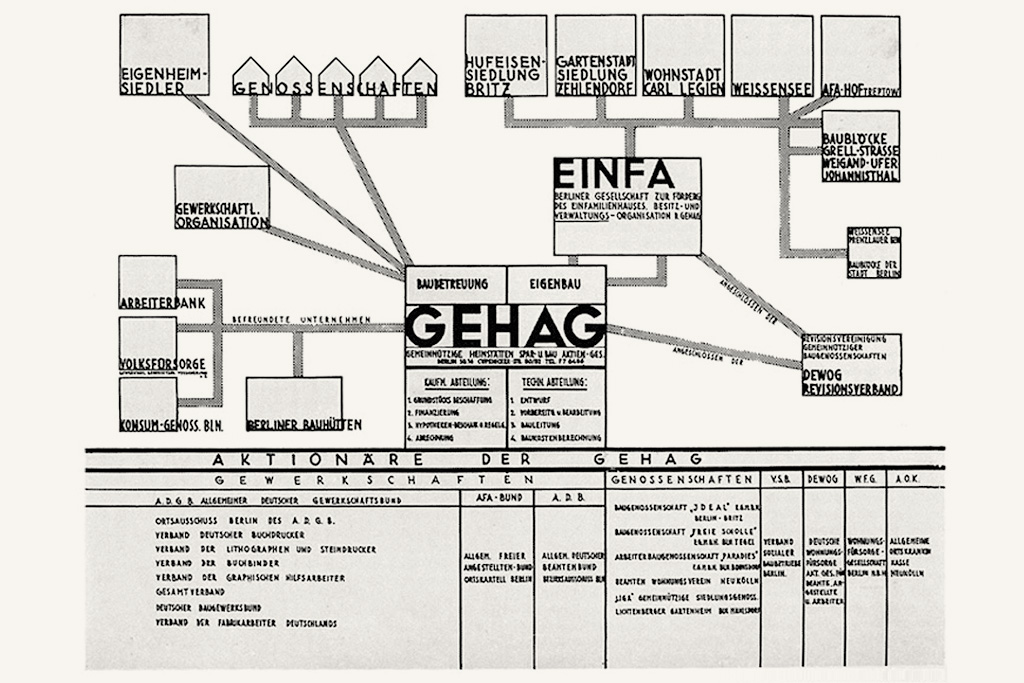

A cooperative is a special form of community ownership used by some 1920s housing estates for their construction and management. Similar to a joint-stock company, a cooperative issues shares to its members who become co-owners of the property. This way, the members share in the costs of new construction, maintenance and administration. In return, they receive preferential rights to apartments owned by the cooperative, and ones that are in the process of being planned or built. Today, two of Berlin’s World Heritage housing estates are still owned by the registered housing cooperative Berliner Bau und Wohnungsgenossenschaft von 1892 eG. Apart from purely cooperative administrations, however, there were also mixed forms such as cooperative banks that invested in housing associations, as was the case when GEHAG was founded. Apart from the building industry, the cooperative model exists in other business areas to jointly manage savings and operations. Some commercial, trading, manufacturing and agricultural enterprises are often fully owned by members of a cooperative. Smaller cooperatives tend to be self-governing, but larger ones tend to elect professional managers.

DEGEWO > association

The name is a German abbreviation for the German Society for the Promotion of Housing Construction. DeGeWo was founded in Berlin in 1924 and unlike its competitor GEHAG, had closer links to German civil servants’ associations than to employees’ organisations. Its first major project was a section of the Horseshoe Estate, which is part of the Large Housing Estate Britz.

Berlin’s city council divided the 37-hectare Britz estate into two sections to be developed by DeGeWo and GEHAG, a move that reflected the political powers of the time. As the Horseshoe Estate was being built, Britz became a theatre of competing ideologies, styles and types of organization. The design of the DeGeWo section was entrusted to the traditional architectural practice of Ernst Engelmann and Emil Fangmeyer, while the building work itself would be carried out by a private company. In its section on the eastern side of Fritz-Reuter-Allee, DeGeWo created stately facades with dormers, expressionist decor and gable roofs, while on the western side of the street, Bruno Taut created architecture for GEHAG which served as a radical visual counterpoint.

During the post-war period, DeGeWo was deeply involved in Berlin’s reconstruction. Prominent large-scale DeGeWo projects of the 1960s and 1970s included Gropiusstadt in the south of Neukölln and a complex on Schlangenbader Strasse in Berlin-Wilmersdorf, where an entire apartment block was built directly over a motorway. Today degewo, whose name is now written in lower case, manages around 75,000 properties, making it the largest state-owned housing company in Berlin.

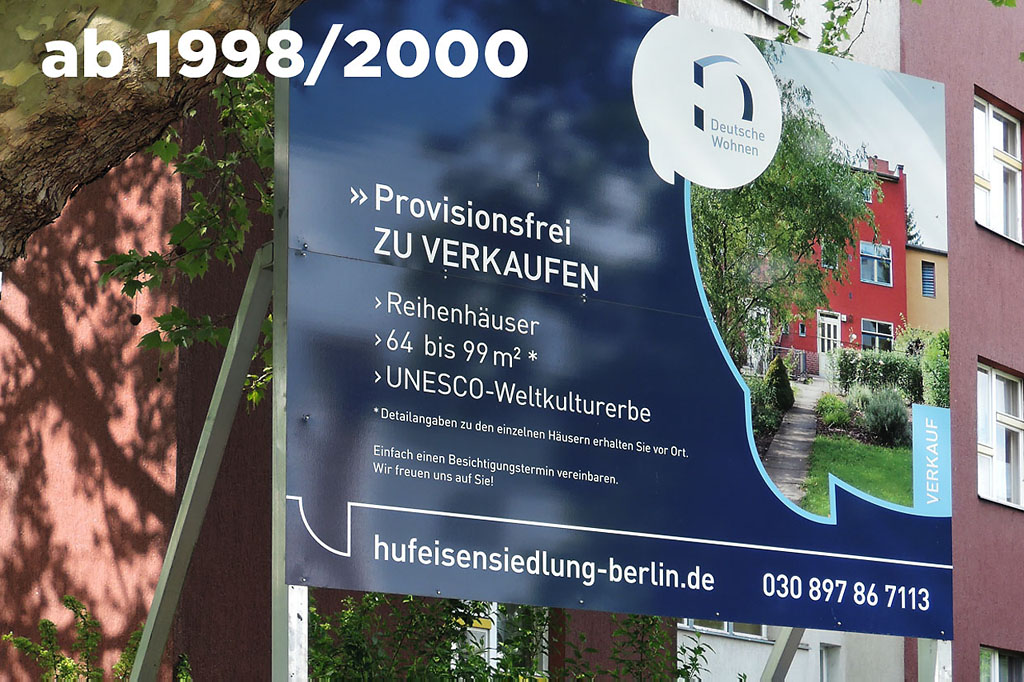

Deutsche Wohnen > company

Founded by Deutsche Bank in 1998, Deutsche Wohnen is a publicly listed residential property company, now Germany’s second-largest following a series of targeted acquisitions. With around 100,000 apartments in its portfolio, it is the largest landlord in Berlin. Deutsche Wohnen has numerous properties once owned by GEHAG, the municipal housing company that hired Bruno Taut as its chief architect upon its founding in 1924. GEHAG was privatised by the Berlin state government in 1998, the result of a political decision that is now difficult to fathom given the city’s current tight housing market and rapidly rising rents.

Following a number of takeovers on the financial markets and targeted purchases of GEHAG’s erstwhile holdings, Deutsche Wohnen became the largest owner of World Heritage housing estates in Berlin. Its portfolio includes the Carl Legien estate, Siemensstadt, nearly all of White City and all multi-storey residential buildings in the Horseshoe Estate (the remaining homes have been mostly converted into private properties). Deutsche Wohnen sees itself as an heir to the GEHAG tradition and in recent decades has invested vast sums in the preservation of its listed buildings. The company spent almost €23 million ($25.4 million) to restore the Onkel-Toms-Hütte housing estate in Berlin-Zehlendorf under the preservation rules for listed buildings, although the estate narrowly missed inclusion on the list of UNESCO World Heritage Sites in 2008.

Nevertheless Deutsche Wohnen, which has a profit-oriented rental policy, has been subject to much criticism in politics and the media. Points of contention include the refurbishment of the Otto Suhr Estate and the purchase of sections of Karl-Marx-Allee planned in late 2018. However, no such concerns were raised in 2013, when Deutsche Wohnen acquired the former municipal housing company GSW and its extensive stock of rental housing.

Another takeover took place in 2021, when the two biggest German real property owners merged and Deutsche Wohnen SE became part of the Vonovia SE.

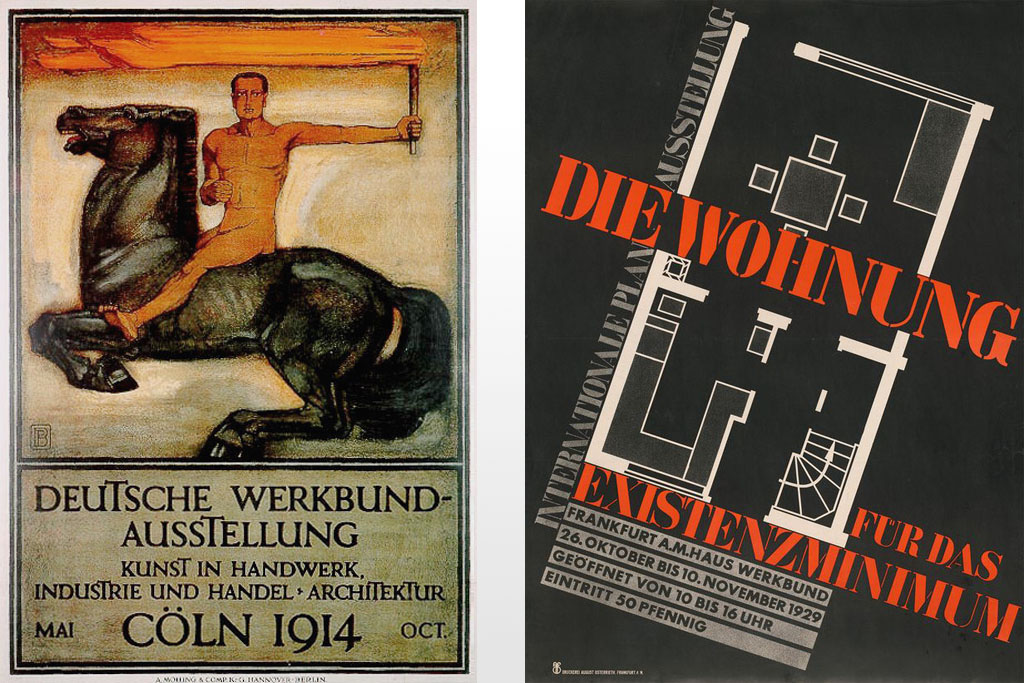

Deutscher Werkbund > estates

The craftsmen’s association Deutscher Werkbund and some members built their own housing estates in a number of German and European cities. The idea was to allow the public to experience the principles of reform housing and New Building first-hand. Similar housing estates exist in Stuttgart, Düsseldorf, Oberhausen, Cologne and Munich, for instance, but others can be found elsewhere in Europe including the cities of Brno, Paris, Prague, Vienna, Wroclaw and Zurich. As a rule, all exhibitions commissioned their own publications and public relations work, thereby attracting great attention. After the Nazis came to power in 1933, the statutes of the association were completely revised and adapted to nationalist thinking. This reorientation prompted many Werkbund members to resign in protest, but others stayed put – partly for career considerations, but also knowing they could rely on conservative and nationalistic sympathies in the reform movements.

Relaunched after the Second World War, the Werkbund is still organized today at the state and regional level throughout Germany. The association has held true to the traditions of its founding years and remains committed to spreading a holistic and Modernist concept of design.

Deutscher Werkbund > members

The founding membership of the craftsmen’s association Deutscher Werkbund read like a “Who’s Who” of prominent designers and personalities of the 1910s and 1920s. These luminaries were architects and planners who later built what would become Berlin’s World Heritage housing estates. Among them were Bruno Taut , Martin Wagner , Leberecht Migge , Ludwig Lesser , Otto Rudolf Salvisberg , Hans Scharoun , Walter Gropius , Hugo Häring , Otto Bartning , Fred Forbat as well as the partly involved planers Max Taut and Heinrich Tessenow. As a pan-German organisation, the Werkbund sought discourse with other champions of the New Building style such as Frankfurt’s urban planning director Ernst May, under whose direction similar housing estates were created. It can generally be assumed, however, that virtually all key initiators of Modernism and New Building were familiar with their colleagues and followed their work closely.

The Werkbund’s relaunch after the Nazi era was widely praised, with backing by key figures of post-war Modernism and political leaders of the newly founded Federal Republic of Germany including the first West German Chancellor, Konrad Adenauer, and the country’s first President, Theodor Heuss. Today’s association in the German capital, the Deutscher Werkbund Berlin (DWB), counts nearly 300 members.

Deutscher Werkbund > organisation

Founded in 1907, the craftsmen’s association Deutscher Werkbund aimed to promote high-quality design. To this end, its members banded together to hash out various issues of art, industry and craftsmanship. The founders also sought to raise recognition for the association’s work among politicians and the general public, and to develop a favorable framework and conditions for production. The association thus combined several reform movements that had emerged during industrialisation. The Werkbund may be regarded as a prototype of a successful lobby organization that eventually extended its activities outside Germany. Shortly after its founding, the association brought together practically all the leading architects and designers of the day (e.g. Peter Behrens, Henry van de Velde and El Lissitzky) as well as prominent figures of industry, politics and the media. Among other things, the association urged a wholesale renunciation of functionless and purely decorative forms, paving the way for the styles New Objectivity and New Building. Indirectly, the association’s work laid the groundwork for a reformed education program such as that offered at the Bauhaus from 1919.

Dry living

For many Berliners at the turn of the 20th century, even the cheapest housing was tough to afford. Many poor people lived either in makeshift cellar apartments or small chambers in the attic – or they shared a bed with other residents as “sleepers”. Another option was the ironically named “dry living”, which was harmful to tenants’ health. Called “dry dwellers”, these lodgers lived in new tenement buildings that officially, were not ready for occupancy before their walls had dried out – which as a rule took three to six months. This was due to the widespread use of cheap lime mortar in the working-class districts, a material that loses large quantities of water as it hardens. Dry dwellers could accelerate the process by heating their homes and simply by breathing. They paid considerably less rent, but had to move regularly and were permanently exposed to moisture, raising the risk of respiratory diseases and colds.

Drying floor

When visiting the World Heritage housing estates, you will notice that most of the larger blocks of flat (or monopitch) roofed apartments have a row of small windows on a compact top floor. This is a communal attic that many residents used to dry their laundry. Most of these squat “drying floors” were just over two metres high and thus of limited use as living space. Some tenants still dry their laundry in them today, although there are no other practical uses – permanent storage and rentals are forbidden due to fire safety regulations. Nevertheless, drying floors are still practical for energy efficiency, because the attic space acts as an extra insulating layer and limits heat loss from the upper floors of the building. An exception is Falkenberg Garden City, where all the homes were fitted with gable roofs when the estate was built in 1913-1916.

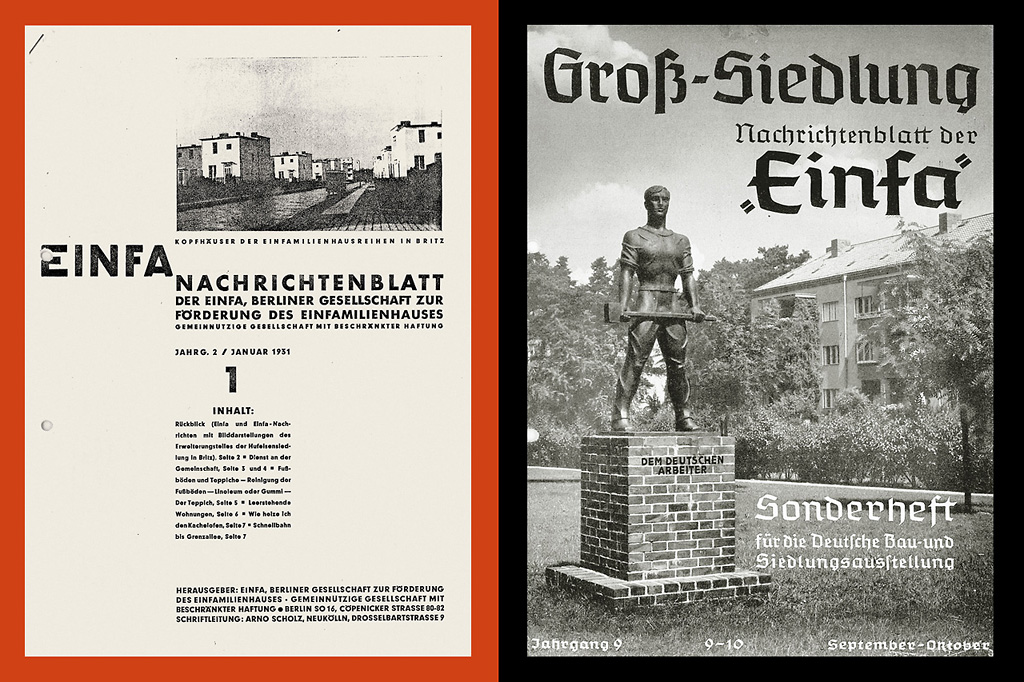

EINFA > association

The Berlin Society for the Promotion of Single-Family Homes, or EINFA for short, was originally part of GEHAG, the housing association founded in 1924. The society was responsible for marketing and letting the housing estates and residential complexes built by GEHAG, and published regular tenant magazines from 1930 to 1938. Initially, these magazines bore the graphic design of Classical Modernism and dealt with matters of contemporary fittings for practical housekeeping, interiors and garden design. From 1933-34, after the National Socialists ousted GEHAG’s management, the layout and topics of the magazine changed. Instead of giving advice on modern living and design, the publication increasingly focussed on Third Reich propaganda. Among the residential facilities rented out by EINFA were the Horseshoe Estate, the Carl Legien estate, and the Onkel-Toms-Hütte estate. The society also let property of the AFA battery factory in Berlin-Treptow and other facilities designed by Bruno Taut in the Berlin districts of Prenzlauer Berg, Weissensee and Johannisthal.

Europa Nostra Award

The Europa Nostra Award is a rare EU heritage prize. Until 2019, the full name was European Union Prize for Cultural Heritage/Europa Nostra Award, which has since been shortened to European Heritage Awards. Since 2002, the EU has been awarding prizes to outstanding examples of successful preservation and communication of architectural heritage throughout Europe.

The Europa Nostra Awards are presented in four categories:

– Conservation (preservation and conservation). Award for Taut’s Home in 2013

– Research

– Dedicated service (special commitment)

– Education, training and awareness-raising

Projects from the Horseshoe Estate have won twice. Taut’s Home, which acts as a rentable museum and holiday home, received one of the rare prizes in the first category. The monument information platform www.hufeisensiedlung.info received an honourable mention in the fourth category. Since 2019 the award is also referred to as the “European Heritage Award”.

European Year of Cultural Heritage

The year 2018 was designated the European Year of Cultural Heritage by the European Union, creating a framework to launch and promote projects that communicate the architectural and intangible heritage of EU countries. The basic idea of the theme year was, although many monuments have local ties, they also remind us of Europe’s common cultural history. Strengthening the culture of monuments not only helps us to understand our own regional or national roots, but also strengthens our awareness of European history and the value of peaceful coexistence characterized by mutual respect. The slogan “Sharing Heritage” invites everyone to discover, share or visit these monuments.

This website has also been supported by the Sharing Heritage Programme. See the imprint for more details.

An overview of other interesting projects can be found on www.sharing-heritage.eu.

Functionalism

Popular at the turn of the 20th century, Functionalism is a philosophy of architectural design holding that form should be adapted to use, material and structure. From the Functionalist point of view, good, timeless design refrained from anything impractical or purely decorative, thus rejecting any forms that were ornate or historicizing. Its proponents believed design should not be guided by visual preferences, as these were always subject to fashion and the spirit of the times. The value of good design was not measured by an item’s visual appeal, but by its utility value, durability, low production costs, suitable materials, and sound ergonomics. In 1890, American architect Louis Henry Sullivan coined the movement’s guiding principle – “form follows function” – which has been quoted ever since (see Bauhaus style, Modernism, New Building and reformed housing). To this day, Functionalism is slammed by its opponents as being cold and unfeeling.

Garden city > movement

The concept of “garden cities” goes back to Ebenezer Howard, an English theorist who published his seminal book Garden Cities of to-Morrow in the early 20th century, initially only in English. His aim was to counter rising land prices, poor housing and deplorable living conditions in the inner cities. Observing the rapid growth of Britain’s industrial cities and the slums that sprouted on their outskirts, Howard proposed building small and medium-sized housing estates in the countryside. He developed a special plan for a “garden city”, which was to serve as a model for its layout. Shortly thereafter, the first garden cities were founded in England.

Translated into German, Howard’s book aroused great interest among German social reformers, green and urban planners. Howard’s ideas quickly developed into an influential model of reform-oriented housing construction in the early 20th century. Both in England and in Germany, “garden city movements” emerged to turn Howard’s ideas into reality while developing their own regional modifications. The first prominent German garden cities were Dresden-Hellerau and Essen-Margarethenhöhe. The reformist slogan “light, air and sun” became popular in Berlin, a city of tenements, and encapsulated many aspects of the garden city concept.

Attempts were made to transfer the concept to the German capital. Two reform-minded landscape architects of Berlin’s World Heritage housing estates helped to develop local garden cities: Leberecht Migge, who co-designed the garden-city-like estate at Lindenhof in Berlin-Schöneberg, and his colleague Ludwig Lesser, who planned the outdoor facilities of Falkenberg Garden City and Staaken Garden City, a community in Berlin-Spandau. Lesser also designed the greenery and open spaces in the then-garden city Berlin-Frohnau, which was laid out in a similar structure. However, Frohnau is more of a colony of villas and country houses than an actual garden city.

Other Berlin sites with garden city character are the Freie Scholle housing estate in Berlin-Reinickendorf, New Tempelhof Garden City (also known as the Aviators’ Estate) and the residences around Rüdesheimer Platz.

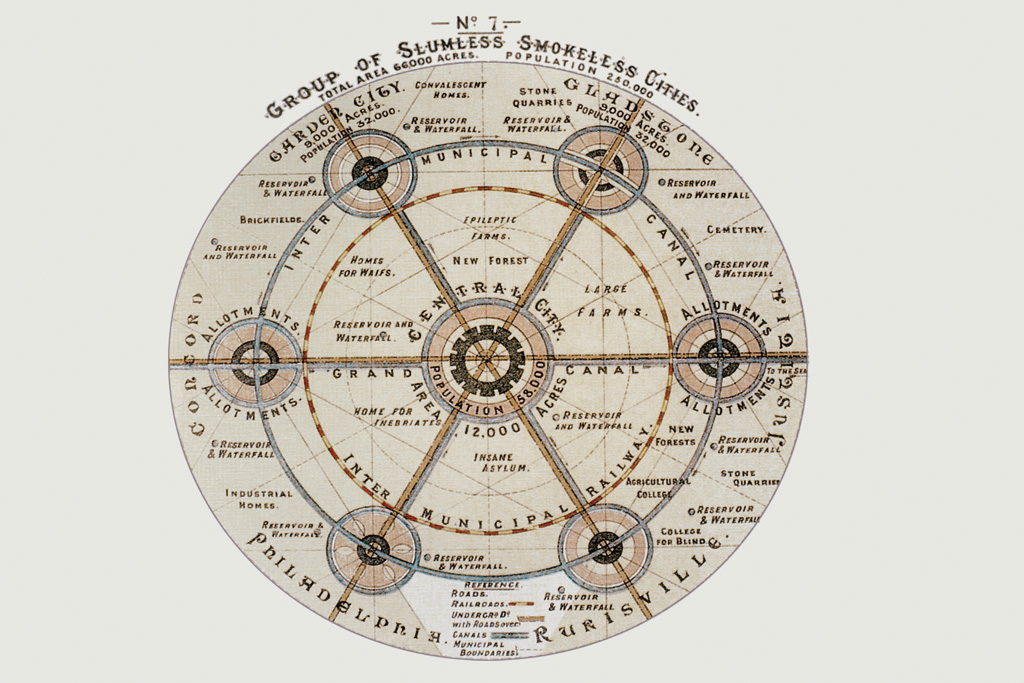

Garden city > scheme

English theorist Ebenezer Howard developed a very detailed and exacting scheme for the ideal layout and realisation of garden cities. Public buildings would be located right in the centre and integrated into a green space. A ring of estate “cores” was planned, each separated from the others by greenery and farmland. These cores were to be connected by a star-shaped railway network radiating from the city centre. The high street would be a place for vital infrastructure such as schools, kindergartens, churches and shops. Industrial production facilities, on the other hand, would be situated outside the cores and the overall community. The gardens would promote self-sufficiency among the residents.

An important aspect often forgotten today was the financing model: Howard proposed that all profits made on the conversion of farmland into building plots should be managed cooperatively and should flow into community development. He also emphasised administration and community organization. Even if his central layout of a garden city was strictly geometrical, Howard’s blueprint was otherwise not set in stone. The size of the city and number of inhabitants were not predetermined; in principle, the model could be applied both to urban populations and to smaller communities. Two of Berlin’s six World Heritage housing estates have central squares, the design of which is based on garden city principles.

GEHAG > association

In Berlin, special public housing associations were set up to reorganise residential construction. The best known of these was the Gemeinnützige Heimstätten, Spar-, Bau und Aktiengesellschaft or GEHAG, which played a decisive role in building the city’s World Heritage housing estates. Founded in 1924, the company had a structure as complicated as its name: a lobby-friendly model that catered to trade union, cooperative, non-profit and municipal shareholders. The politically left-leaning GEHAG was not only in charge of planning, design and financing, but also had its own non-commercial property developer, Deutsche Bauhütte, and therefore did not have to hire profit-oriented construction companies. The marketing and letting of GEHAG properties were handled by the Berliner Gesellschaft zur Förderung des Einfamilienhauses, or EINFA for short. Bruno Taut, who designed four of Berlin’s six World Heritage housing estates, was engaged as chief architect for consulting and design. The first chairman of the supervisory board was Martin Wagner, an architect and Social Democrat who was a driving force in the planning and reorganisation of Berlin housing construction. Wagner was appointed municipal building commissioner in 1926. GEHAG’s transformation during the Third Reich is a prime example of how the Nazis pressured people and organisations to tow the party line. Only a few months after Hitler came to power, all of GEHAG’s managers were suddenly replaced, which naturally had an impact on the association’s leasing policy.

In 1998, GEHAG was privatized by the State of Berlin despite fierce protests from tenants. Following a series of takeovers on the stock exchange, GEHAG became part of the Deutsche Wohnen group. Due to takeovers on the stock market in 2021, the two biggest German real property companies merged and Deutsche Wohnen SE became part of Vonovia SE. From the social and the preservation perspective, the initial sale of GEHAG resulted from a political decision that is difficult to fathom today.

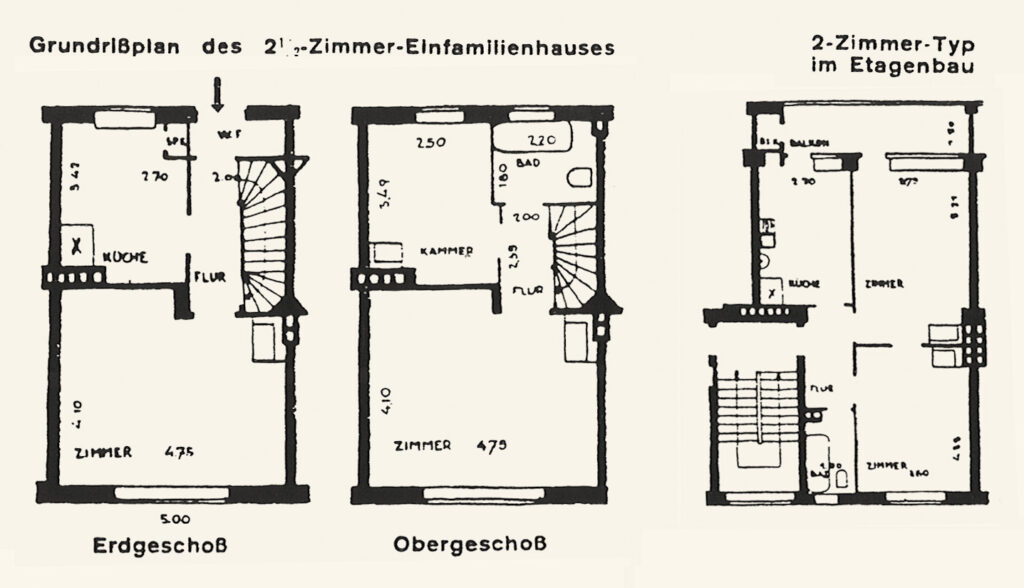

GEHAG > Floor Layouts

The floor plans of the GEHAG housing association, which were considered to be particularly space-saving, were largely developed by its chief architect Bruno Taut or the head of the GEHAG design department Franz Hillinger. They were mainly used in multi-storey apartment buildings, but also in terraced houses in some estates – such as the Hufeisensiedlung Britz or the Waldsiedlung Zehlendorf. The GEHAG floor plans were slightly adapted for various estates and special situations. They exist in various standard sizes with one and a half to four and a half rooms. Typical of the floor plans, however, is always the focus on a high quality of living and maximum use of space. The apartments in the multi-storey buildings usually have a loggia, a kind of enclosed balcony, which Taut also referred to as an “outdoor living space”. The loggia adjoins one of the central living rooms. Some loggias are also accessible from the kitchen. Ideally, the loggia faces away from the street towards a quiet, often semi-public green space. Depending on the type of urban development, GEHAG’s terraced houses – as well as some of the first floor apartments – have access to their own garden with a terrace next to the house.

The apartments are accessed via a short, almost square hallway. From here, the individual, rather small and similarly sized rooms branch off. In the case of terraced houses, behind the entrance there is a so-called “vestibule” with space for a checkroom, from which the staircase leads directly to the stairwell with an elegantly curved but rather steep staircase. In multi-storey residential buildings, the kitchen and bathroom are generally oriented towards the stairwell because the impact sound is less disruptive here. In keeping with the guiding principle of light, air and sun, all apartments and houses are lit from both sides so that the rooms can be efficiently ventilated across. Each bathroom also has its own small outside window to prevent damp and establish better hygiene standards. Larger floor plans have several rooms of roughly the same size, which can be used as bedrooms, living rooms or children’s rooms, depending on preference and family situation.

A single unit in GEHAG’s multi-storey apartment buildings is around ten meters wide and has three to four residential floors. They are usually organized as so-called “two-floors”. This technical term means that there is one apartment to the left and one to the right of each landing of the central stairwell. Towards the roof, there is usually a half-height “drying floor” that closes off the building at the top, where tenants can dry their laundry. The individual units, each with a separate entrance door, can be strung together to form long rows of identical or almost identical units.

The structural standard of the GEHAG buildings is very solid: all buildings have a full basement. The exterior walls generally consist of 24-38 centimetre thick brick walls, which are finished on the outside with colored plaster. All living rooms, bedrooms and kitchen windows are designed as “wooden box double windows” with two casements. At the time of construction, all living rooms and bedrooms were generally heated by tiled stoves, which had to be positioned next to the chimney flue for smoke extraction. To save space, the stoves were often placed behind the opening room doors. In the post-war period, the striking, often colorful tiled stoves were removed almost everywhere as part of the switch to gas central heating.

GEHAG > privatisation

The privatisation of Berlin municipal housing company GEHAG reads like an economic crime thriller. The 1998 sell-off seems all the more surprising today, given the capital’s tight housing market and rapidly rising rents. GEHAG was founded to build affordable housing for the lower and middle classes, and this pledge shaped its culture and corporate policy. But the Berlin government, led by the Social Democrats, nonetheless decided to sell GEHAG and its holdings of prestigious monuments to ease the city’s beleaguered finances. The company was sold by auction and the procedure was subject to a number of legal conditions; bidders who were deemed unsuitable were excluded in advance. The contract was awarded to a relatively small property company, RSE Grundbesitz und Beteiligungs-GmbH, which grew out of the railway builder and operator Rinteln Stadthagener Eisenbahn AG. The latter had a tradition of building housing estates for its plant workers.

The selling price for GEHAG’s properties was around €1,000 per square metre, extremely cheap by today’s standards (current market prices are around €5,000 per square metre). Shortly thereafter, however, RSE was taken over by Hamburg-based WCM Immobilien-Holding, a property company that had been excluded from bidding. In quick succession, there were several takeovers of GEHAG’s favourably priced portfolio on the stock market, and properties designed by Bruno Taut in the Horseshoe Estate briefly appeared in the portfolios of US hedge funds such as Oaktree Capital Management and Blackstone Capital. In the course of their ownership changes, these properties – comprising nearly 700 terraced houses, which up to that point had been leased – were gradually sold off to individual private owners, a policy maintained today by Deutsche Wohnen, the last major buyer of Horseshoe Estate properties. This now means that the Horseshoe Estate has one large proprietor (Deutsche Wohnen still owns 1,263 apartments there) and well over 600 individual private owners. This fragmentation has made it much more difficult to uniformly preserve the finely tuned World Heritage Site, leading residents to develop their own private projects. These include the Infostation in the Horseshoe Estate and a large, web-based database dedicated to the preservation of the estate.

Guided tours

There are no regular guided tours without prior booking or registration. However, there are a number of private organisations and small companies (like the main author of this website) who offer guided tours and/or architectural walks through the UNESCO World Heritage “Berlin Modernism Housing Estates” upon request. These can be identified via search engines and local websites like hufeisensiedlung.info as well as via a special touring event page within Facebook.

A free opportunity to visit the estates is usually provided by the so-called “Day of the Open Monument“, which in Berlin always takes place on the second weekend in September and offers a broad program of visits and guided tours in German language.

Information can be obtained from the operators of the [glossary key=”infostation-siemensstadt”]Infostation Siemenststadt[/glossary] and its counterpart, the [glossary key=”infostation-hufeisensiedlung”]Infostation Hufeisensiedlung[/glossary]. Here, people interested in monuments, tourists and neighbours can obtain information on the history of the estates on certain occasions. Furthermore, interested parties can contact Berlin´s tourist agency visitBerlin.de or the regional tourist information offices of the respective districts.

Please note

All six World Heritage estates are residential areas. This requires appropriate consideration. Walking paths, general behaviour and extensive photo taking that could disturb the privacy of the residents needs to be avoided.

Hot water supply

To qualify for subsidies from Berlin’s house interest tax (1924), every new apartment had to have a private bathroom – a must for proper reformist housing and the city’s new quality standards. For the less well-off, this was nothing short of a revolution. However, the technology of the day could not deliver the comforts that we now take for granted. For example, the bathrooms in the Horseshoe Estate were equipped with coal-fired water heaters. Installed on the wall above the bathtub, these cylindrical tanks had a lower berth where a small stove was placed to heat water for a hot bath. To wash their clothes, some residents had access to special laundry cellars or washhouses.

ICOMOS > organisation

The International Council on Monuments and Sites, ICOMOS, is a non-governmental, transnational organization founded in 1965. The World Heritage Convention from 1972 advises UNESCO on issues of monument and cultural property protection. Tasks include the preparation of expert reports for the World Heritage Committee to consult when deciding on new entries for the UNESCO World Heritage List. ICOMOS is also responsible for ongoing conservation reviews of registered World Heritage Sites and for identifying critical developments. To this end, so-called “monitoring tours” of the Berlin World Heritage Sites are carried out at regular intervals. As of 2019, the organisation had national committees in more than 120 countries with 20 to 30 scientific committees dedicated to special areas, regions, eras or monument categories.

Inflation

Inflation describes a currency’s sustained loss in value and purchasing power. Simply put, inflation makes everything more expensive, as the exchange rate falls and the value of money decreases. A rapid devaluation had dramatic consequences in Germany as purchases of daily staples such as bread or milk ate up more and more wages, as was the case from 1914 to 1923. During the extreme inflation of 1923, the value of money fell so fast that Germans hurried to buy groceries after receiving their monthly pay. Prices rose hourly.

The crisis forced the housing associations and their architects to make building projects more cost-efficient. The resulting cost cuts affected the design and construction of World Heritage housing estates built from 1928 onwards.

Infostation > basic touristic facilities

On two of Berlin’s World Heritage housing estates, old retail shops have been converted into so-called Infostations. Both locations are owned by the Deutsche Wohnen property group, which runs the premises and rents them to the operators on favourable terms. Here, tourists, neighbours and monument enthusiasts can beef up on the history of the residential estates.

Infostation Siemensstadt

Located at the corner of Goebelstrasse and Geisslerpfad, this office is run by photographer Christian Fessel and the architectural firm Ticket B, a Berlin guided tours specialist and a partner in the Horseshoe Estate. The Siemensstadt Infostation has a small book shop, café, and 3D model of the housing estate plus public conveniences. Special exhibitions with architectural photos are held on occasion.

Opening hours and details of guided tours or events are available by telephone (030-2885252-1).

Infostation Hufeisensiedlung

Located at 44 Fritz-Reuter-Allee in the right-hand head building of the Horseshoe complex, this facility is the go-to source for anyone interested in World Heritage Sites. It is run on a voluntary basis by the association Friends and Sponsors of the Horseshoe Estate Berlin-Britz, founded in 2007 during the initial privatization of the estate. A café serves drinks and homemade cakes, plus there is a bookstore. The rooms host a permanent bilingual exhibition on the Horseshoe Estate’s past and present (created by the main author of this website). Brief details on Berlin’s other five World Heritage housing estates as well as selected planners and residents round out the offering. A special catalogue and bilingual architecture guide are available for the exhibition. A typical GEHAG Kitchen can also be viewed on site. Postcards and locally made products are sold, and cultural events are held on the premises.

Opening hours: Fridays and Sundays, April to September: 2-6 pm. October to March: 1-5 pm. See more details at hufeisensiedlung.info.

Additional services

In addition to the two Infostations above, there are other ways to explore the housing estates. For example, Falkenberg Garden City and the Schillerpark Estate have a visitor guidance system with information points plus some basic details, site maps and 3D models. Siemensstadt also has its own information boards.

In the Schillerpark Estate there is a brief panel-based exhibition in the former public conveniences next to the Plansche (wading pool). The key can be obtained from the nearby concierge service of the World Heritage Room at Oxforder Strasse 4.

The museum Taut’s Home in the Horseshoe Estate is available for rent, enabling architecture lovers to spend a few nights at the World Heritage Site. Run by two private individuals, the property is a house with garden designed entirely in the 1920s style of architect Bruno Taut. Restored in its original colours with a strict adherence to monument preservation rules, the museum doubles as a holiday home and sleeps up to four guests. The property has won several monument awards. Casual visits for sightseeing are not possible. See further details at tautshome.com.

Infostation > Hufeisensiedlung (Southeast)

This Infostation is located at 44 Fritz-Reuter-Allee in the right-hand head building of the horseshoe complex and is part of the tour through the Hufeisensiedlung.

The best go-to location for anyone interested in World Heritage Sites, the office opens every Friday and Sunday afternoon. It is run on a voluntary basis by the local association of the Friends and Supporters of the Horseshoe Estate (Freunde und Förderer der Hufeisensiedlung Berlin-Britz e.V.), which was founded in 2007 during the ongoing privatisation of the estate. In the front, there is a café serving drinks and homemade cakes, and a bookstore is attached. The back rooms host a permanent bilingual exhibition on the Horseshoe Estate’s history. Brief details on Berlin’s other five World Heritage housing estates as well as selected planners and residents round out the offering. A special catalogue and bilingual architecture guide have been published for the exhibition. A typical GEHAG Kitchen can also be viewed on site. Postcards and locally made products are sold, and cultural events are held occasionally.

Opening hours

- Fri + Sun afternoon

- April – September: 2–6 p.m.

- October – March: 1–5 p.m.

Further information in German language:

hufeisensiedlung.info.

Infostation > Siemensstadt (Northwest)

Situated at the corner of Goebelstrasse and Geisslerpfad, the Infostation Siemensstadt is run by photographer Christian Fessel and the architectural firm Ticket B, a specialist in Berlin guided tours and a partner of the Horseshoe Estate. The Siemensstadt facility houses is a small book shop, a café, a 3D model of the housing estate and public conveniences. There are also occasional exhibitions with architectural photos.

Opening hours and the terms for guided tours or organizing events can be obtained by telephone (030-2885252-1).

International Style

In the early 20th century, various parts of the world saw avant-garde movements emerge, some of which pursued similar goals. In Germany, the craftsmen’s association Deutscher Werkbund and the Bauhaus design school merit a special mention. But in Russia, the Czech Republic and the Netherlands, similar groups had already made a name for themselves and advocated a radical renewal in art and design. With the rise of the National Socialists and the Second World War looming on the horizon, many German and European champions of the Classical Modernism and New Building movements went into exile and spread their ideas abroad, where their approaches were adapted to the region and climate. In 1932, an exhibition was held at the Museum of Modern Art (MOMA) in New York, bringing together different trends in modern architecture of the 1920s and 1930s from all over the world. The organizers named the exhibition International Style, which then established itself as a concept in its own right.

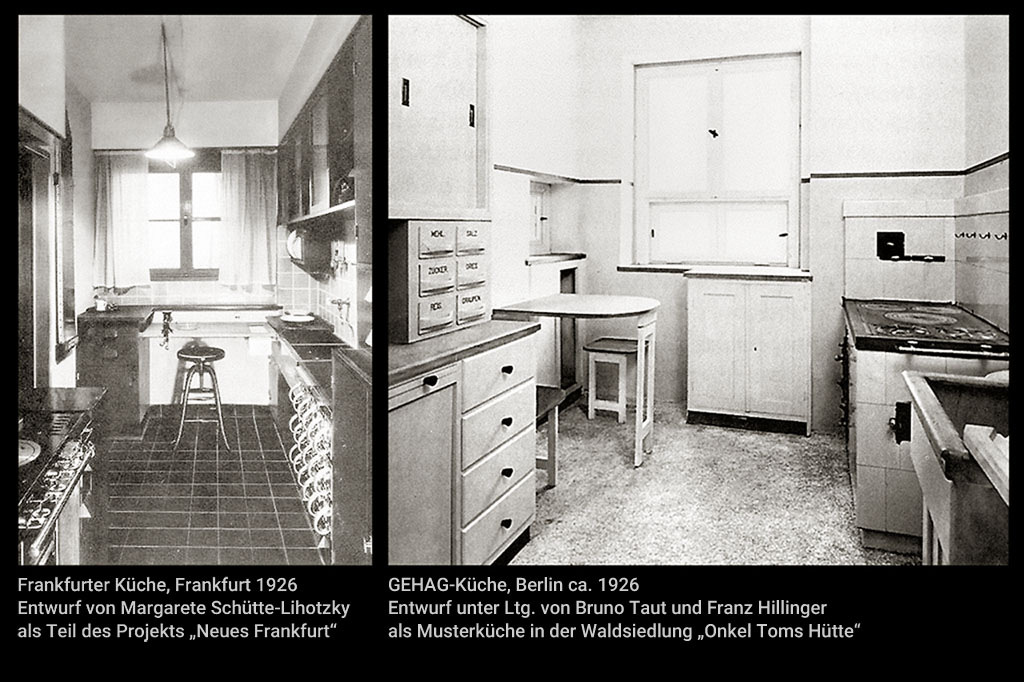

Kitchen design > Frankfurt Kitchen

It is interesting to compare the so-called Frankfurt Kitchen (1926) with contemporary alternatives such as the GEHAG Kitchen. The model in Frankfurt am Main, which great influenced fitted kitchens of the post-war years, was designed by architect Margarete Schütte-Lihotzky and emulated the New Building style. The blueprint foresaw an elongated U-shaped kitchen of about 6 to 8 square meters. The idea was to make routine work processes as efficient as possible, which had a direct impact on the design and arrangement of the furnishings. For example, there were many so-called “chutes”, small containers for frequently used foodstuffs such as flour, salt or sugar. They were integrated into kitchen cupboards as small labelled drawers and could be pulled out and used like jugs for pouring. There was also a fold-down ironing board and a rack for drying crockery. The design was intended to relieve the housewife’s workload and took a cue from the efficiencies of industrial production, as on a factory assembly line. Unlike Bruno Taut’s GEHAG kitchens in Berlin, the Frankfurt Kitchen was rather cramped and designed for one person only. Although it was also designed to reduce typical “women’s work”, it cemented the role of the housewife who prepared the food and took care of the family’s domestic needs.

Kitchen design > GEHAG Kitchen

Although no specific kitchens were commissioned for Berlin’s World Heritage housing estates, Bruno Taut, the architect in charge of four of the six properties, developed a show kitchen around 1926 with Franz Hillinger of GEHAG’s design department. It was intended solely for the Onkel-Toms-Hütte housing estate in Berlin-Zehlendorf, but became a standard kitchen on quite a few of Berlin’s World Heritage housing estates. The GEHAG Kitchen by Taut and Hillinger is a combined dining area and working kitchen. Besides a kitchen unit and a large multi-purpose cupboard, it has a small folding table with seating for family members to perform little chores such as peeling potatoes. This design allowed typical household roles to be relaxed.

Taut was concerned about the role of women in the household, but this was probably out of self-interest: like most architects, Taut wanted the houses and apartments he designed to be modern and stylishly furnished. Taut assumed that women made most of the key interior design decisions, so he tended to address them instead of the male audience. In his pioneering book Die Neue Wohnung (The New Home) published in 1924, Taut tried to convince women to make their homes as modern and rational as possible, since this would save time and work. “The architect thinks, the woman directs” became an oft-quoted catchphrase from the introduction of Taut’s book. Today this sounds like a limited form of emancipation, but back then, it was nothing short of daring.

An original GEHAG Kitchen from the Zehlendorf estate can be viewed in the Horseshoe Estate’s Infostation, a café-cum-exhibition space open every Friday, Saturday and Sunday afternoon. The kitchen in Taut’s Home was based on the GEHAG version and is fully available to guests as part of the rental.

Kitchen design > Haus am Horn

The first influential kitchen design of the 20th century appeared in this experimental model residence built in Weimar in 1923. The original design was by Georg Muche, head of the weaving class at the Bauhaus design school. Haus am Horn and its interior design would be used to test and demonstrate Bauhaus principles. The staff of Walter Gropius’ architecture office planned the details, and practically all individual Bauhaus workshops contributed to the furnishings. Perched on a hill, the house was anchored by a central entrance room and designed for a family with no paid help. The kitchen design is essentially an L-shaped countertop with some upper and lower cabinets and a sink with a base cabinet. Kitchen fittings were faithfully reproduced but later supplemented with modern appliances, such as a microwave or electric hot water boiler. The property now doubles as an event venue and was reopened to visitors in 2019 after a four-year renovation.

Krugpfuhl Estate

In the UNESCO World Heritage overviews you will find the entry “Britz Large Housing Estate/Horseshoe Estate” – a double-barrelled label that is a source of confusion, also for Berlin’s monument list. The residential area here was developed by two housing associations, resulting in two separate housing estates, the Horseshoe Estate and the Krugpfuhl Estate. Only the Horseshoe Estate, however, is registered as a World Heritage Site and an ensemble monument. The Krugpfuhl Estate was built at the same time (1925-26) by the DeGeWo housing association and is part of the buffer zone around the neighbouring World Heritage Site. It is exciting to compare two estates where local style and Modernism meet head-on.

Labour movements

From the mid-19th century onwards, many industrial companies settled in Berlin and its environs. Although these factories brought new jobs, industrialisation also aggravated poverty, as the prices of non-industrially manufactured products fell. Craftsmen, agricultural and textile workers were hit as their goods could no longer compete on price. Many workers changed jobs and sought work in large factories, causing the industrial workforce to expand. Karl Marx, the great social theorist, called this emerging working class the “proletariat”. He was referring to simple people who had almost nothing to offer but their labour and were forced to earn their living by “selling” it. To assert their interests, workers organised themselves in trade unions despite their members’ dependence on powerful factory owners. These unions demanded higher wages, more security, greater social justice and better living, working and housing conditions.

Many ordinary factory workers elected candidates from left-wing parties, such as the Social Democratic Party of Germany (SPD) and the Communist Party of Germany (KPD), which held a combined majority on the Berlin city council in the 1920s. Left-wing parties called for more housing construction, to be financed either by the public sector or through cooperatives. These demands came as working-class living standards were in decline in cramped tenement blocks.

In Germany, housing associations were then founded to create pleasant, affordable housing for the lower and middle classes.

Large housing estates

Called “Grosssiedlung” in German, the term “large housing estate” applies to new residential facilities of more than 1,000 apartments. According to this definition, three of Berlin’s six World Heritage housing estates qualify as large housing estates, namely the Horseshoe Estate, White City and Siemensstadt.

Loggias

In common speech, loggias are a kind of balcony that graces most rental apartments at Berlin’s six World Heritage estates. Unlike a regular balcony, a loggia often has walls on two sides and usually a ceiling (except for the loggias on the top floor). The window bays appear as rectangular cut-outs that are drawn forward from the rest of the building. The origin of the term loggia goes back to Renaissance buildings and has linguistic and historical links to the words “lodge” or “arbour”. In the warmer countries of southern Europe, loggias often take the place of balconies because the former reduce the incidence of sunlight.

Modernism

As an adjective, “Modernist” describes a period of architecture and the new style and thought associated with it. In the field of art history, Modernism refers to the work of artists, designers and architects who sought to develop a new language of form in the early 20th century, thus opposing the conservative traditionalists and historians. Many German advocates of Modernism were later branded “degenerate artists” or “cultural Bolshevists” by the National Socialists, who invoked an allegedly original German design and character. The Modernists were persecuted and many went into exile.

To distinguish between the style developments of the Modernist period, sub-concepts emerged for the different phases. As a rule, Modernism is considered to have begun at the turn of the 20th century, a phase that is simply referred to as Early Modernism. Buildings dating from around 1920 to the mid-1930s and the rise of National Socialism are considered the core style and were thus categorised as Classical Modernism. However, there was an enormous number of radical breaks and reform movements that pursued similar goals in parallel. After the Second World War, attempts were made to pick up where this successful period left off. From that time on, the individual decades are used as labels, such as “1950s Modernism” or the Modernism of the 1960s or 1970s. Only from the early to mid-1980s was Modernism considered to have come to an end in terms of historical ideas.

In architecture, art history and philosophy, Post-Modernism followed, meaning “after” Modernism. Typical characteristics of Post-Modernism are citations and combinations of well-known set pieces from different historical eras. A similar thing occurred in pop music, as people in the 1980s and 1990s talked about post-punk and post-rock. In the field of architecture, there are many parallels between Classical Modernism and reform housing, New Building, Functionalism and Bauhaus style, labels often used by experts in art and architectural history.

The term Modernism is similarly applied in the social sciences and in the realms of literary and scientific history. The works of Albert Einstein, Sigmund Freud and Franz Kafka, for example, are attributed to Modernism because these men broke radically with established ways of thinking, explanatory models and narrative structures.

Monopitch roofs

The term refers to the predominant roof form in the World Heritage housing estates. Strictly speaking, a monopitch (or pent) roof is the most common variation of the flat roof. The usual inclination of a monopitch roof is about 4 degrees, just enough to allow rainwater to run off to one side. This model has two distinct advantages: First, it increases useable living space on the upper floor and second, construction is much cheaper than for a traditional triangular gabled roof, which is elaborately tiled by hand. However, proponents of traditional design thought it strange to ditch the triangular gable and roof truss, and fierce disputes erupted between the two camps. Construction of the Horseshoe Estate, for example, was halted when it became clear that gables, which were perceived as typically German, should be eliminated from the design of the “Red Front” section of homes. The same conflict was bitterly thrashed out around the leafy housing estate in Berlin-Zehlendorf called Onkel-Toms-Hütte. The “Zehlendorf Roof Controversy” pitted traditionalists of the neighbouring Fischtalgrund Estate against advocates of the Modernist housing style as practised by Bruno Taut, Otto Rudolf Salvisberg and Hugo Häring.

Monument > categories

In the realm of monument protection and preservation, a distinction is made between the following categories:

• architectural monuments (e.g. the television tower on Alexanderplatz)

• ground monuments (e.g. excavations of Berlin’s first settlement at Petriplatz)

• garden monuments (e.g. the Grosser Tiergarten)

• monument ensembles (e.g. the Horseshoe Estate)

• industrial monuments (e.g. the AEG turbine hall)

• art monuments (e.g. sculptures in public spaces)

• listed interiors (e.g. interior furnishings)

• natural monuments (e.g. beech woods or raised bogs)

• intangible cultural property (e.g. bread baking, choral singing or carnival) and

• lea monuments (e.g. areas with historical wall or path systems – mostly in rural areas).

Monument > listed in Berlin

Any building, garden, object, ensemble or structure that is representative of a certain style or era can be listed as a historical monument. It is then registered and entered into a so-called monument list. This procedure ensures that important cultural records are preserved as faithfully as possible, and that registered monuments may not simply be altered or demolished without permission. As a rule, the respective state authorities decide on the registration of an object; to ensure a precise classification, they have established several categories of monuments. How a monument and/or cultural property should be maintained and preserved is usually regulated in monument maintenance plans drawn up by experts specifically for these objects. In Berlin, the lower monument protection authorities of each district are in charge of monitoring the proper preservation of monuments.

In Berlin there are about 8,000 registered monuments, of which about one-third date from the 20th century – an unusually high percentage internationally. The highest possible status of a monument is a registration as a UNESCO World Heritage Site. Germany has 44 World Heritage Sites, three of which are in Berlin. This figure is also unusually high and gives Berlin, along with Rome and Mexico City, the top position in a comparison of global cities as of 2019.

To learn more

- All Berlin monuments can be researched online in the database of the Berlin Monument Authority.

- The second weekend in September, many Berlin monuments are opened to visitors and for guided tours during Open Heritage Day. These tours often go to places that are otherwise not open to the public.

Onkel-Toms-Hütte Estate

A leafy housing estate in south-west Berlin known as Onkel-Toms-Hütte (Uncle Tom’s Cabin) is one of Germany’s most famous. It is also among the biggest of Berlin’s 1920s residential estates, with around 1,900 units built in seven construction phases in 1926-31. Besides Bruno Taut, the chief architect of the GEHAG housing association, architects Hugo Häring and Otto Rudolf Salvisberg, as well as landscape architect Leberecht Migge, were involved in the project. Contrary to the expectations of many experts, the property in Berlin-Zehlendorf – often called a “forest estate” because it blends into the natural wooded environment – was not included in the city’s initial application for World Heritage listings of its housing estates. Onkel-Toms-Hütte was excluded mainly because of architectural conversions in many of the estate’s terraced dwellings, which meant they did not meet requirements for listed buildings. However, the site still qualified as an ensemble monument, as these conversions were carried out earlier. Unlike the terraced homes at Onkel-Toms-Hütte, which are privately owned, all of its rental apartments belong to a single owner, Deutsche Wohnen, which extensively restored the ensemble in the 2010s. World Heritage is currently considering a nomination to add the estate to Berlin’s existing listings. In terms of the overall design, colours, layout and style of individual components, Onkel-Toms-Hütte has numerous parallels to the slightly older Horseshoe Estate in Berlin-Britz. Because of its vibrant colours, Onkel-Toms-Hütte was dubbed “Parrot Estate” by some Berliners (see the section “Cheeky Berlin nicknames” in the Siemensstadt section).

Despite its absence on the World Heritage list, Onkel-Toms-Hütte is still considered one of Bruno Taut’s major works. A survey of the estate by the architecture workshop Pitz-Brenne begun in the late 1970s led to a series of studies, restorations and monument registrations.

Open Heritage Day

The World Heritage housing estates cannot be visited on guided tours without prior notice. Fortunately, doors to these properties are thrown open for free on Open Heritage Day, a Europe-wide event. Due to the wide range of activities on offer, Open Heritage Day in Berlin is always held for two days on the second weekend in September. You can find details on the Internet and choose from a variety of visits and guided tours. Tours are free of charge but often require advance registration.

Some tour operators offer guided visits of the World Heritage sites all year round, either for a fee or by donation. For legal reasons, the publisher of this website cannot make any recommendations, but the relevant operators are easy to find via search engines.

On the Horseshoe and Siemenstadt estates, old shops have been converted into so-called Infostations where tourists, residents and monument enthusiasts can obtain background details of the estates. Interested parties should contact visitBerlin and the district tourist offices across the city.

NOTE

These World Heritage Sites are residential areas. Architecture and history enthusiasts are respectfully asked to show consideration and avoid taking photos, using private paths or otherwise conducting themselves in any way that could disturb the privacy of the residents.

Reform-orientated housing

This is a collective term for various initiatives which, from the mid-19th century onwards, called for an overhaul of housing construction in terms of design and concept. Germany’s reform housing construction had its roots, among other things, in the garden city movement that spread from England to mainland Europe around 1910. It is thus closely linked to the founding of housing associations and the ideal of “light, air and sun” that was pursued in Berlin. Unlike the advocates of New Building, however, the proponents of reform housing stuck to traditional building methods and materials instead of relying on concrete, glass, extensive standardisation and mass production. From today’s perspective, it is instructive to see how the construction of reform housing estates was cleverly linked to pre-defined quality standards and the new house interest tax.

Rotating maps

Please note that the map shown during the “Tour” sections can also be rotated or tilted. To call up the 3D simulation on PC or Mac systems, please go into the picture with the mouse button pressed down and simultaneously hold down the following keys on the computer keyboard:

- Windows PCs: hold down/move the ctrl key + mouse button

- Mac computer: hold down/move the alt key + mouse button

- On the Smartphone: Here only zooming in, zooming out and rotating is possible. To rotate, select the symbol with the two triangles

and move the map with two fingers.

Service paths

These narrow footpaths linked the private gardens of the Horseshoe Estate and Falkenberg Garden City with the rubbish tips and other commons areas. This secondary network of paths complemented the roads, a solution that was both pleasant and practical. Thanks to the service paths, garden waste did not have to be carried through the house. Another key advantage, especially from today’s point of view, was that these paths created extra space for children to meet and play. This was especially useful because the rise of car ownership in the 1920s meant that the city’s streets and sidewalks became much more dangerous as potential playgrounds.

Sleepers and lodgers

Inexpensive housing in Berlin was so scarce that subtenants shared up to half of all the city’s cheap apartments. These lodgers were mostly single men who – in keeping with their shifts at the factory – alternately shared a bed with two or three other men, thus the nickname “sleepers”. One can imagine how a shift worker returning from night duty would stretch out in the still-warm bed of his colleague or landlord, who would then set off for the early shift. Families often depended on subletting beds to strangers during the day in order to supplement the household budget.

Slogan “Light, air and sun”

This auspicious slogan brought together reform-oriented planners and architects at the beginning of the 20th century. Their goal of “light, air and sun” meant creating a healthy living space in an unconstrained, green environment. This architecture was designed to eliminate the misery in the often crowded, dark and stuffy rear courtyards of tenement blocks. “Light, air and sun” often turns up in discussions about Modernist 1920s housing, and is closely related to models of public parks and reform housing. Many of these ideas influenced the design of the gardens, green spaces and open areas of Berlin’s World Heritage housing estates. These estates outdid the New Building standards of other European hubs, thanks to the efforts of landscape architects Ludwig Lesser and Leberecht Migge, who served as chief planners. Both men helped to lay out two of the city’s six World Heritage housing estates, and they ensured that their designs were highly practical – to promote social contact in the community, and to grow fruit and vegetables.

Tenement blocks

Due to their tenant-unfriendly design, droves of tenements built in late 19th century Berlin quickly got a bad reputation. Most of them were cheaply made, five-storey structures financed by private investors. They were located inside so-called “block edge developments” that occupied the front of entire street blocks. Behind the smart street facades, tenement gardens or other open spaces were gradually filled in to accommodate ever more tenants and boost rental income during the city’s great housing shortage of the 1920s. This type of complex dominated the landscape of Berlin’s working-class districts such as Moabit, Wedding, Kreuzberg, Neukölln, Friedrichshain and Prenzlauer Berg. The inner reaches of these huge blocks were typically built around a series of courtyards.

Typically, Berlin tenement blocks had one or two cheaply-constructed side wings followed by a cross-wing, which was in turn followed by another courtyard, and so on. Such complexes were often several courtyards in depth. According to the legal requirements of the day, these rear extensions could be very narrow: legally, an inner courtyard did not have to be more than five-and-a-half metres wide, the clearance needed for a horse-drawn fire engine to turn around. In a complex of one to two storeys, you might not find that space narrow, but because the bulk of Berlin’s tenements were higher – generally five storeys with an average height of about 22 metres – these properties felt cramped.

The “New Building” style

The German terms “Neues Bauen” (New Buidling style) and “Neue Sachlichkeit” (New Objectivity) refer to certain design principles of reform oriented artists and designers of the early 20th century. They are used by art historians as fixed terms to define a certain style that stands out from the historicism of previous eras.

Disciples of the New Building style sought a new approach to architecture in a rejection of established methods. “Old” construction was seen as employing useless decorations on historicised facades. Similar to the Modernists, the advocates of New Building sought to dispense with purely decorative elements in order to find a new language of form – one that was distilled to function, essence and transparency. They rejected the excessive decoration of bygone eras because it arose from the needs of the monarchy and nobility to project prestige, something that simple people would then try to imitate with modest means. This approach was considered outdated, dishonest and undesirable. The political spirit of the age was to question the class system while strengthening democracy and the labour movement – ideals that did not sit well with the upper-middle class and pompous nobles. Instead, clearly structured, brightly lit and transparent buildings should emerge in order to reflect the Age of Enlightenment, industrialisation and progress. The ideals of New Building thus had strong ideological parallels to Functionalism and the spirit of Modernism.

Housing estates designed by the craftsmen’s association Deutscher Werkbund played a special role in the New Building style. Although actually habitable, these dwellings were built for demonstration purposes in Germany and some neighbouring countries. The Werkbund’s most famous estate is located in Stuttgart-Weissenhof in south-west Germany, a joint experimental project of several prominent architects in the organisation. Apart from this partly preserved complex in Stuttgart, cities with New Building estates in Germany include Düsseldorf, Oberhausen, Cologne and Munich, while elsewhere in Europe, sites can be found in Brno, Paris, Prague, Vienna, Wroclaw and Zurich. Some of them, too, have been only partly preserved.

It should be noted that many of these progressive ideals had a slight totalitarian streak: not only did they seek to build a better future, but sometimes to demolish the past. Time and again, the stucco of richly decorated facades was removed purely for the sake of creating something new. This was known as “de-decoration”, a process that affected large parts of the Prenzlauer Berg and Kreuzberg districts in Berlin, which at the turn of the 20th century still had a considerable number of stucco facades.

The “New Man”

The early 20th century was a time of social awakening when almost everything was supposed to be “new” and different. Not surprisingly, there were also many reform movements aimed at creating a “New Man” who would ideally be social, cosmopolitan, enlightened, tolerant, modern, healthy and energetic. These movements sought to question value systems, discard false ideals, focus on a healthy lifestyle, and gear design and architecture more towards function and utility. When creating a home environment, planners should avoid bourgeois status symbols and purely ostentatious design as much as possible.

Type construction