Schillerpark Housing Estate (1924–30)

The social dimension

Facts and Figures

- Location: District Mitte, locality Wedding

- Public transport: U Rehberge

- Streets: Barfusstrasse, Bristolstrasse, Corker Straße, Dubliner Strasse, Oxforder Strasse, Windsorer Strasse

- Total area of world heritage: 4.6 ha

- Total area of additional buffer zone: 11.37 hectares

- Number of apartments: 303 with 1-1/2 to 4-1/2 rooms each (excluding kitchen and bathroom)

- Constructed: 1924 to 1930

- Project management: Martin Wagner

- Urban design: Bruno Taut

- Architects: Bruno Taut, reconstruction/completion

by Max Taut (1951) and Hans Hoffmann (1953 until 1957) - Landscape architect: Presumably Bruno Taut,

from 1954 Walter Rossow - Developer: Berliner Spar- und Bauverein (construction 1924-1925 by GEHAG – Gemeinnützige Heimstätten-, Spar- und Bau-AG)

- Reconstruction: From 1991, with an emphasis on architectural preservation

- Owner in 2009: Berliner Bau- und Wohnungsgenossenschaft von 1892 eG

- Tenants in 2009: (ca.) 740

- Monumental category: Ensemble-Monument

Message

The Schillerpark, which lent the estate its name, was laid out in 1909-13. Starting in 1924, a completely new type of architecture was created north-east of the park: instead of a closed block with several staggered backyards, the apartments here boasted living rooms and balcony-like loggias with views of a spacious green area, right in the thick of the city. The corners of the street blocks were kept clear so the air can circulate better. The front doors of most homes were not on the street, but rather in inner areas, reached either via corner accesses or from the green courtyard. Playgrounds for children and rest areas were part of the concept. Rubbish sheds were discreetly integrated into the complex, and apartments had separate bathrooms and kitchens, representing a significant improvement in hygiene standards. Thanks to these simple but revolutionary changes, the basic features of the estate met the newly defined quality standards for reform housing. The estate offered a pleasant and relaxed living environment, with plenty of opportunities for social interaction. Bruno Taut, the architect, called it an "outdoor living space".

Design

The Schillerpark Estate is part of the surrounding English Quarter, as is apparent from the streets named after British (and some Irish) cities. Dutch names would actually have been more appropriate, because the estate’s design paraded the close links between leading German designers and their colleagues in the Netherlands. In 1923, Bruno Taut took a research trip to Amsterdam and Rotterdam, two important centres of Modernist housing construction. The designs of his Dutch colleagues J.J.P. Oud and H.P. Berlage, in particular, inspired Taut. After studying their work, Taut opted to use visible red brick and flat roofs, the latter still an unusual feature at the time. Unlike the other five World Heritage estates in Berlin, the property suffered severe damage in the Second World War. With styles of two eras virtually side by side, it is easy to see how the Modernist extensions of the 1950s expanded on the design ideals and models of the 1920s while setting new accents, for example in the selection of colours, materials and windows.

History

The Schillerpark Estate was the first Berlin housing estate to be planned and built entirely in the New Building style, thus setting a new standard in architecture and urban development. Like Falkenberg Garden City, which was built before the First World War, the Schillerpark Estate was financed by the Berliner Bau- und Sparverein, a cooperative bank and building society. Anyone could become a member and acquire long-term residential rights by paying regular instalments of savings or deposits, and unlike the construction financed by private investors, these projects tended not to attract speculators. The house interest tax, which was introduced in 1924 to finance residential construction in the public interest, was applied here for the first time. In 1951, reconstruction of the war-torn buildings was led by Bruno Taut's younger brother, Max. From 1954 to 1959, the estate was expanded significantly under plans by architect Hans Hoffmann and landscape architect Walter Rossow. Since 1994, the ensemble has been listed as a historic monument; a year later, it was also registered as a garden monument. In 2010-11 the park and buildings were extensively restored.

Social Issues

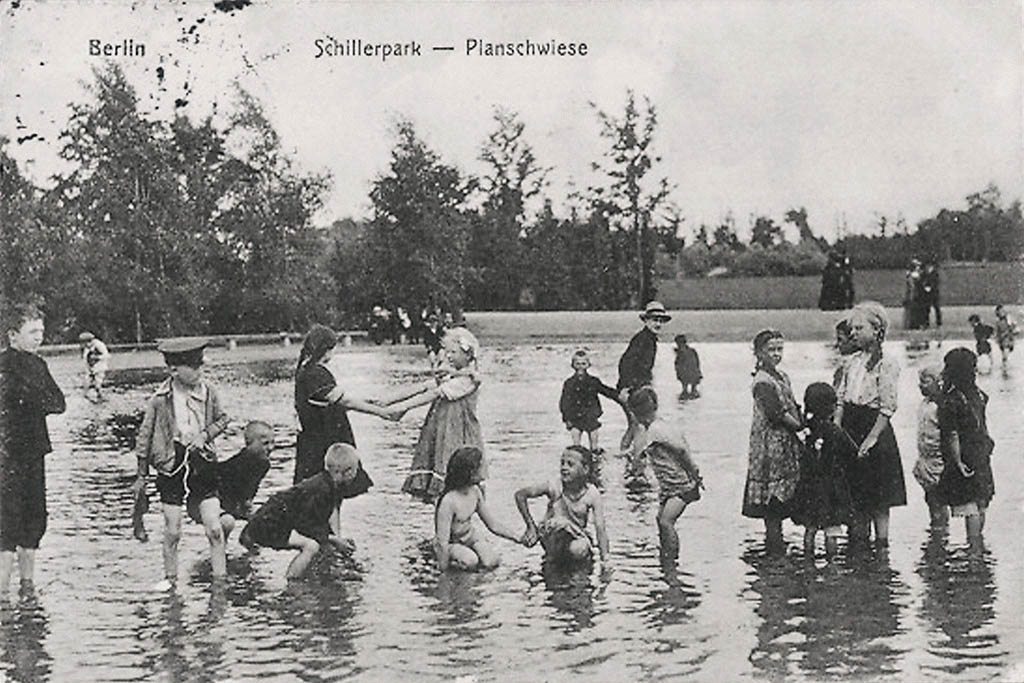

We take it for granted today, but the idea took a surprisingly long time to catch on: that parks should provide space for simple sporting activities, playgrounds and sunbathing. "Keep off the grass" signs were no longer in step with the times. Instead, relaxation, destressing and exercise were the order of the day. Laid out between 1909 and 1913, the Schillerpark Estate incorporated the first modern Volkspark and perfectly suited a new generation of architects and planners who strove for "light, air and sun" and exercise for the masses. Unlike Falkenberg Garden City, a rural, ecological development laid out almost a decade earlier, the Schillerpark Estate had no fancy terraced house gardens for growing fruit and vegetables. By comparison, this housing estate with flat-roofed apartment blocks in Berlin’s inner-city district of Wedding was immediately more urban and modern. With its communal open spaces and play facilities, the estate sports facilities for families with children or stressed city dwellers, and blends nicely into the neighbouring park.

In the early days of the Schillerpark Estate, it had a consumer-goods shop, a washhouse and a kindergarten. They no longer exist today, but social considerations remain a priority, starting with the ownership structure and operational model. Built in 1924, the estate is still run by a cooperative, meaning there is no single profit-oriented owner. The "comrades" or co-owners hold shares in the company's property portfolio, creating a shared feeling of solidarity. In the Wedding district, the World Heritage Site was redesigned to create a multi-generational neighbourhood with disabled-access apartments. Because installing or extending lifts was prohibited for reasons of monument protection, barrier-free ramps for wheelchair users, which are hardly visible to the naked eye, were installed in some ground-floor units. In addition, the cooperative built some special buildings on an adjacent plot of land in 2012, allowing older residents to remain in their old neighbourhood.

Places worth seeing

Further information

Quiz Questions

- When was the Schillerpark created?

- Which role models did the estate have?

- How was the construction financed?

- What did Max Taut plan in 1951?

- What was Franz Hoffmann's nickname?

- How did some apartments become barrier-free?

Links and Resources (selection)

- Registered in the List of monuments

- Registered in Wikipedia

- Landesdenkmalamt Berlin (Ed.): Berlin Modernist Housing Estates / Siedlungen der Berliner Moderne, Berlin 2009 (D/E)

- Jörg Haspel / Annemarie Jaeggi (Ed.), Markus Jager (Author): Berlin Modernist Housing Estates, Berlin 2007 (D/E)

- Landesdenkmalamt Berlin (Ed.), Sigrid Hoff (Author): Berlin World Cultural Heritage. Beiträge zur Denkmalpflege in Berlin, Bd. 37, Berlin 2011 (D/E)

- Stadtwandel Verlag (Ed.), Lars Klaaßen (Author): World Heritage Sites Gartenstadt Falkenberg / Schillerpark-Siedlung Berlin, Die neuen Architekturführer No. 166, Berlin 2011

- Deutscher Werkbund (Ed.), Winfried Brenne (Author): Bruno Taut – Master of colourful architecture in Berlin, Berlin 2008

- Kurt Junghanns: Bruno Taut 1880-1938. Architektur und sozialer Gedanke, Leipzig 1998

- Wolfgang Schäche (Hrsg.): 75 Jahre GEHAG 1924–1999, Berlin 1999

- Harald Bodenschatz, Klaus Brake (Hrsg.): 100 Jahre Groß-Berlin, Bd. 1 – Wohnungsfrage und Stadtentwicklung, Berlin 2017

- Michael Bienert / Elke Linda Buchholz: Die Zwanziger Jahre in Berlin. Ein Wegweiser durch die Stadt, Berlin 2015

- Ben Buschfeld: Bruno Tauts Hufeisensiedlung – and the UNESCO World Heritage Site "Berlin Modernist Housing Estates", Berlin 2015 (D/E)

Please note: Resources in italics are only available in German.