History of Berlin

Preliminary stages of today's Greater Berlin

Berlin teems with evidence of Germany’s past: merchants, electoral princes, kings, emperors, chancellors, artists and dictators all came to the capital to take up residence. Again and again, you come across squares, buildings and other sites where major historical events occurred. Many of them are monuments that bear witness to key political and social developments. In the 1920s, when Berlin’s six World Heritage residential estates were built, things really took off. Below are the most important stages of its evolution, from Germany’s founding to the division of the city shortly before the Wall was built.

1237 — The origins

The name Berlin is derived from the Slavic language and means roughly “swamp” or “wet place”, referring to the relatively soft ground in the city centre. For large construction projects in the inner city, these conditions continues to cause structural problems, additional costs and delays. But sometimes the advantages and disadvantages go hand-in-hand: the swampy soil has to do with the fact that the three rivers Spree, Dahme and Havel converge in Berlin and form different tributaries. These watery arteries provided transport connections for the boats of the merchants and early settlers.

A typical "old town" does not exist in Berlin. On the contrary: apart from a few excavation sites, no architectural evidence has been preserved of the actual core of Berlin. The historical origin of the city lies a little southwest of Alexanderplatz and is located in the area that we perceive today mainly as a large traffic intersection, the former dairy market called Molkenmarkt. Somewhat to the north-east stands the Nicolai Church. Although it originated around 1230, it was modified several times in the course of the centuries. The surrounding Nicolai Quarter (named after the church) is even more curious. Rebuilt by the former GDR government on the occasion of Berlin’s 750th anniversary, the area consists of a wild mix of vaguely historic, prefabricated concrete buildings and genuinely historic 18th-century townhouses. The only thing that is truly old in the Nicolai Quarter is the urban layout. If you want to take a look at very early Berlin, visit the excavations at Petriplatz or the Museum of Pre- and Early History.

Separated merely by the Spree river, a dual city developed at the beginning of the 13th century, consisting of Old Berlin in the north-east and Cölln along the south-west of the Spree. First officially documented in 1307, this urban area quickly grew into an important trading centre in medieval times. In 1486, Berlin became the seat of the Brandenburg Electors and in the early 17th century, the capital of Prussia. But the Thirty Years' War soon left Berlin struggling. By the end of the war in 1648, the population had halved and its buildings lay almost completely in ruins. A massive fortress wall was built around the city. Due to targeted recruitment efforts by Prussia, the numbers of Huguenots and Jews in Berlin increased sharply. However, development took off only after the start of industrialisation: after 1850, the population of the region rose sharply. The city grew in leaps and bounds after 1920, when Greater Berlin was founded by merging several neighbouring towns, villages and rural communities under a single administration. A pleasant side effect of this unification was the sudden availability of large swathes of new building land – a precondition for the emergence of the World Heritage housing estates.

Special places

Nicolai Church

Excavations at Petriplatz

Gertraudenbrücke / Mühlendamm

Molkenmarkt / Old Town House

1709 — Royal seat of Prussia

Prussia’s rulers showcased their power by erecting a spate of new buildings. This was reflected in the names they chose: around 1730, the city was extended along Friedrichstrasse to create Southern Friedrichstadt. Three prominent squares that bordered the new area to the west and south were given specific geometric forms: Pariser Platz at the Brandenburg Gate was designed as a perfect square, Leipziger Platz was octagonal and Hallesches Tor, at the southern end of Friedrichstrasse, was round. In the late 17th century, the area of Berlin comprised what are now the districts of Mitte and Kreuzberg. At the time, the city was surrounded by a 17-kilometer (10.6-mile) wall. To this day, the names of many places and public transport stops refer to the old gates along this wall. If you trace a line through Oranienburger Tor, Frankfurter Tor, Schlesisches Tor, Kottbusser Tor and Hallesches Tor on the underground map, you get a fairly accurate idea of where the city limits were.

Besides well-known streets such as the Unter den Linden boulevard, prestigious residences and administrative buildings, many other parts of the city were built under Prussian rule. These included industrial estates, schools and irrigation and sewage systems. The proposals of Prussian urban planner James Hobrecht extended far beyond the city limits and proved to be quite favourable for future construction projects. His development plan of 1862 provided the blueprints for Berlin's water supply and traffic management that are still in use today.

Special places

Unter den Linden

Brandenburg Gate

Humboldt University (in the former Prinz-Heinrich-Palais)

Several public transport stops near the former town wall

(Oranienburger Tor, Frankfurter Tor, Schlesisches Tor, Kottbusser Tor und Hallesches Tor)

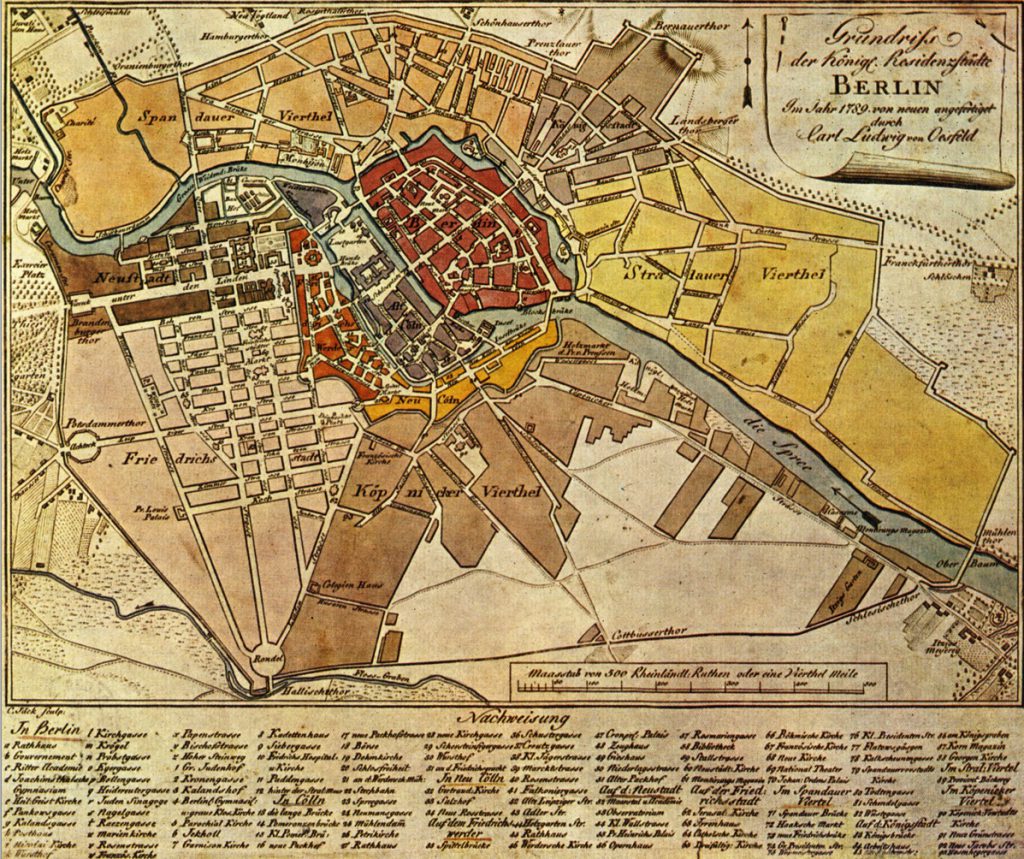

City map of 1789

For non-Berliners, the historic map of Berlin of 1789 may seem somewhat confusing at first. The maps shows references to a Spandauer Quarter and a Köpenick Quarter. However, they does not refer to the historic city centres and present-day districts, as both areas are now part of the Mitte and Kreuzberg-Friedrichshain districts respectively. These names were chosen only because roads ran through the districts and linked the much older towns of Spandau and Köpenick. Even the tiny area marked "Neu Cöln" (New Cöln) in yellow has nothing to do with today's district of Neukölln.

Good to know

Not everything in Berlin that looks historical actually is. The city’s history is one of constant destruction and replacement, or rather, a history of changing reconstruction. The re-creation of the Nicolai Quarter and of Berlin’s royal palace in the heart of the city are prime examples of this practice. The facades of the monumental palace, which now houses the Humboldt Forum, were indeed modelled on the Berlin City Palace of the Hohenzollerns that once stood here. At the same time, however, the new building was arguably a questionable act of justice by the political victors. During the Second World War, the original palace burned down and the remains were leveled in 1950 despite protests. In 1973, the modern Palast der Republik was erected on the same spot to host the East German parliament. After the Wall fell, the Bundestag – Germany’s lower house of parliament which consisted mainly of lawmakers from former West Germany – voted in 2003 to demolish the historical Palace of the Republic in favour of this dummy Hohenzollern palace, which re-creates the original historic facades on three sides.

1848 — Failed revolution

Many people were dissatisfied. They suffered great hardship and some lived in inhumane conditions. The number of employees working in industry increased, and the income gaps widened. In the spring of 1848, bloody conflicts broke out in Berlin and its citizens took to the streets to protest against the monarchy and growing inequality. People fought for a uniform German nation-state with a democratic constitution and more social justice. But in March 1848, the uprisings were crushed by Prussian troops under King Frederick William IV. Similar scenes occurred around the same time in many other parts of Europe, as industrialisation led to great social tension in almost all major cities. With the revolutions of 1848-49, however, a process was set in motion in Europe that would determine events on the continent in the long term, resulting in shifting political and national alliances. This situation helped cause the outbreak of both world wars, but also ultimately led to the founding of the European Union. In 1861, Berlin incorporated a number of suburbs including Gesundbrunnen, Wedding, Moabit and parts of Charlottenburg, Schöneberg, Tempelhof and Rixdorf. The population of Berlin grew to about 550,000. This was followed by the construction of the Rotes Rathaus (Red City Hall), which would now serve as the administration of an urban hub measuring almost 60 square kilometres (23 square miles). This richly decorated complex is located on the southwest side of Alexanderplatz and is still the seat of Berlin's mayor.

Special places

Cemetery of the March Fallen in Volkspark Friedrichshain

Red City Hall south of Alexanderplatz

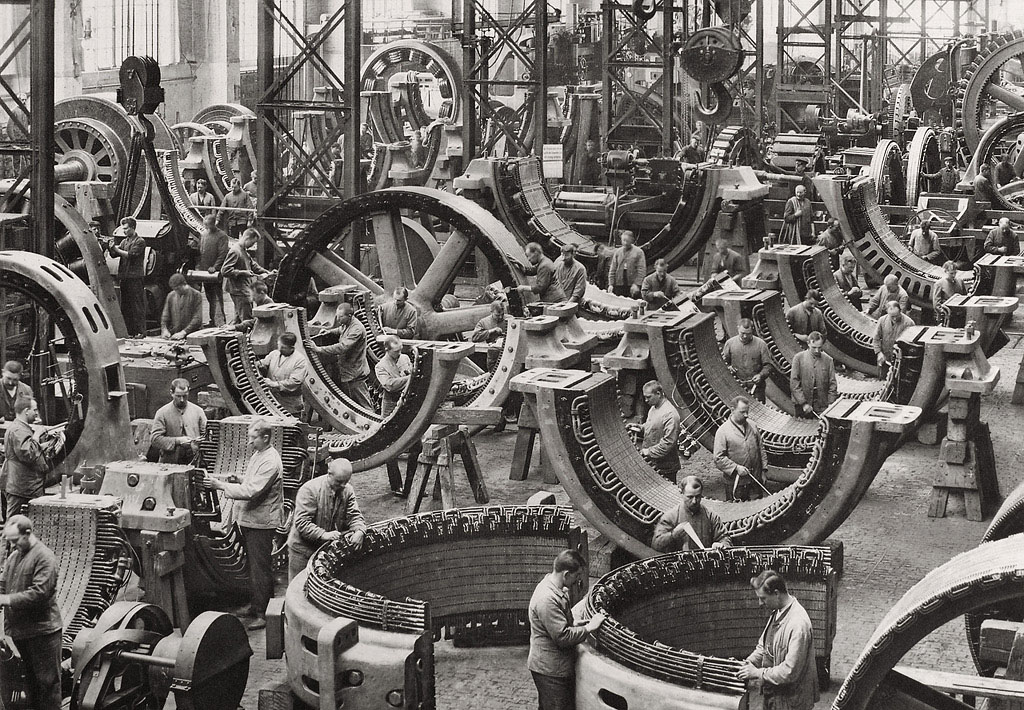

1877 — Industrial metropolis

By 1877, the population of Berlin exceeded one million. In the course of industrialisation, large power stations, industrial plants, factories and other company buildings sprang up around the capital. Together with the associated residential quarters, these activities shaped entire regions and city districts, and many of these buildings still exist today. They include, for example, the Siemensstadt housing estate in the Wedding district and the industrial areas along the Spree in the south-eastern district of Oberschöneweide. Apart from the electrical industry, there were several large companies in Berlin that needed workers and thus fuelled the city’s continued growth. The catalysts included major employers such as the Borsig machine works on Chausseestrasse and the chemicals manufacturer Schering, now part of Bayer Pharma. In 1881, an electrically powered railway went into operation in the Lichterfelde district for the first time. The region began to network technically, economically and politically. After the founding of Greater Berlin in 1920, the culturally aspiring metropolis was the largest industrial city in Europe and at the same time, a stronghold of the labor movement.

Special places

Siemensstadt (n Wedding and Charlottenburg Nord)

AEG turbine hall in Wedding

University of Applied Sciences in Oberschöneweide (former. Kabelwerk Oberspree)

Numerous underground stations and former power stations

1918 — The Weimar Republic

On 12 January 1919, an uprising initiated by various political left-wing groups was brutally crushed. In the early 1920s, Germany’s fledgling democracy struggled with a steep devaluation of its currency and attempts to overthrow the royalists. Reparations paid to other European countries for damages in the First World War weighed heavily on the German treasury. As the unrest continued, in March 1919 there was a large general strike. Almost one million demonstrators, strikers and otherwise dissatisfied individuals demanded further reforms and more co-determination. Thanks to a strong industrial recovery from 1924 onwards, a phase of relative economic stability followed, ushering in a period often referred to as the "Golden Twenties". This era, however, came to an abrupt end with the outbreak of the world economic crisis in 1929.

The brief economic recovery in the 1920s was an opportunity to break new ground in social housing construction. The period between 1924 and 1934 is considered the apex of the New Building movement, which gave rise to five of Berlin's six UNESCO World Heritage housing estates. This phase of progressive building policy ended in 1933, however, when the National Socialists came to power and Adolf Hitler was appointed Chancellor of the Reich. Hitler's preference for a more traditional, “typically German” architectural style, eventually caused a large number of modern architects, artists and designers to lose their commissions and suffer political persecution. Quite a few of them left Germany in the 1930s and went into exile abroad.

Special places

German Bundestag (in the old Reichstag building)

German Historical Museum (in the former royal arsenal)

Tenements and inner courtyards in the workers' districts

UNESCO World Heritage housing estates

1920 — Greater Berlin

In the immediate vicinity of Berlin, many communities and medium-sized towns emerged which are today known as individual districts (Berliners also call them "Kiezen"). In 1908, the first design competitions were held to integrate these surroundings into the urban planning process. Finally, in 1920, seven towns – Spandau, Köpenick, Charlottenburg, Wilmersdorf, Schöneberg, Neukölln and Lichtenberg – plus 59 rural communities and 27 estate districts were combined by resolution of the Prussian state assembly. As a result, Greater Berlin was created with 3.86 million inhabitants. Overnight the region became the third-most populous city in the world, after New York and London. The record-breaking area of 876 square kilometres (338 square miles) was only surpassed at that time by Los Angeles. Unlike on the Californian coast, Berlin’s early focus on expanding public and electrified local transport ensured good accessibility to and within the city despite the great distances involved. But there were also problems.

1923 — Germany’s hyperinflation

In order not to be depleted of gold, an internationally recognised means of payment, the state dissolved the gold standard for banknotes, cash notes and coins, and forbade withdrawals. Since the central bank, the Reichsbank, no longer had to keep track of the equivalent value in gold, it began to print more banknotes to finance the war. At the same time, production for industry and craftsmen became more and more complex and more expensive due to a lack of manpower and materials. After the German Reich capitulated in 1918, inflation soared. As the loser and a chief initiator of the First World War, the Reich government had to pay damage reparations to the victors and bear the costs of their post-war reconstruction. Even with taxes, customs duties and data, the government could not cover the necessary expenditure. It continued to print money and caused the Reich’s currency to slide even further.

Inflation reached its peak in 1923, when it accelerated into so-called hyperinflation. At that time, the banks could not keep up with the depreciation, even by printing banknotes in denominations with ever more zeros attached. In November 1923, a loaf of bread in Berlin cost over 5 billion marks. In this situation, whoever was able switched from currency to barter and demanded payment in items like sausage or bread. The inflation of the 1910s and early 1920s also led to massive differences in wealth in Berlin and growing dissatisfaction among the public, fuelling political unrest during the Weimar Republic. Politicians responded by resorting to measures such as the introduction of a housing interest tax, but the crisis could only be eased by launching a radical currency reform. The Reichsbank was made an institution independent of the German government, and the victorious powers of the First World War agreed to a new financing plan for reparations claims.

1924 — New Building movement

In the early 1920s, 70 percent of Berlin's apartments had only one or two rooms. Many people had also taken up quarters in the cellars or attics. Individual rooms – or even beds not used by the family during the day – were often sublet to strangers. The resulting hygienic conditions were catastrophic, and contagious disease flourished. The construction of new, large, generally affordable living quarters became inevitable. In reform-oriented circles of politics and society, means were sought to make good architecture and design accessible to less well-off sections of the population. In this instance, the craftsmen's association Deutscher Werkbund played a central role. After 1906, almost all the planners and architects who were later involved in Berlin’s World Heritage housing estates regularly met at the association. In Germany and elsewhere in Europe, solutions were sought to the widespread shortage of housing. In contrast to almost all other major European cities, however, Germany’s capital region had two clear developmental advantages that stemmed from the founding of Greater Berlin in 1920. Firstly, Berlin had several city “centres”, each with its own infrastructure; secondly, the enlarged city now had many more areas suitable for building new housing, such as former farmland. While many of the early housing projects undertaken during the 1910s adhered to ideals of the garden city movement, the course has now been set towards a much more urban-looking, space-saving style of large housing estate with linear blocks of flats. Most buildings were constructed with three to five storeys and had a modern flat or monopitch roof. The Schillerpark Estate, built from 1924 in the district of Wedding, was the first Berlin housing estate in the New Building style. But four of the city’s other World Heritage residential sites built in 1924-34 are also attributed to this style.

Special places

Berlin Modernism Housing Estates

Bauhaus Archive / Museum of Design

Werkbund Archive / Museum of Things

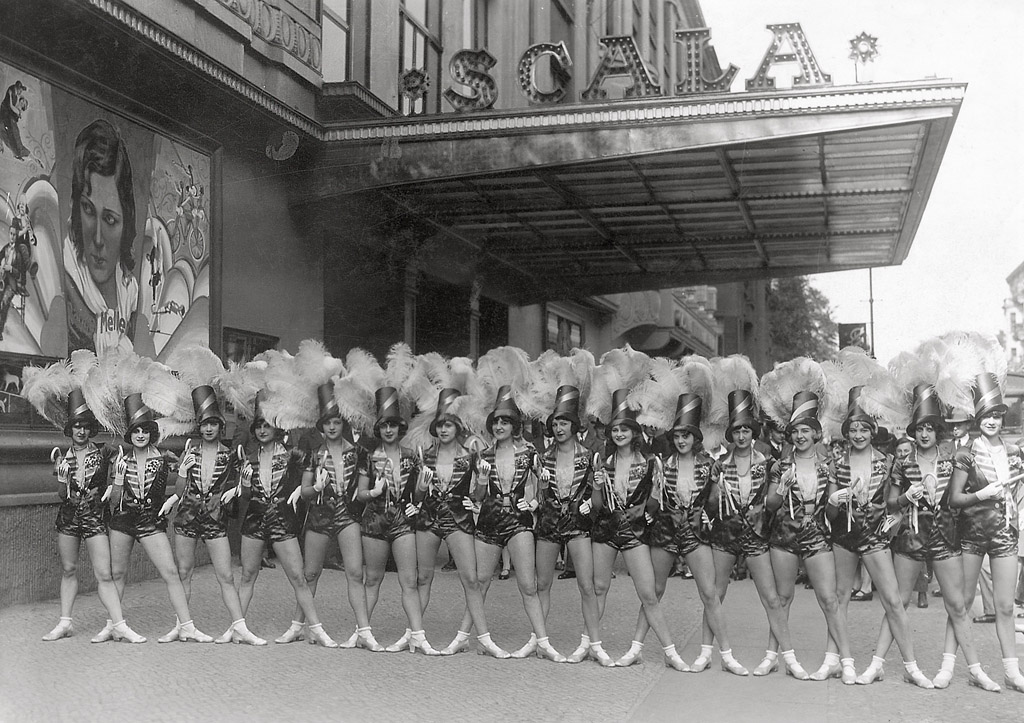

1925 — Golden Twenties

This liberal, event epoch has shaped the image of the city to this day. It continues to provide material for literature and art. A good recent example is the television series Babylon Berlin produced in 2018 (and based on a novel by Volker Kutscher), whose seasons parade the era’s raucous mix of political unrest, gang wars, petty crime, partying, police state, prostitution and domestic misery. The economic conditions were difficult at first, but people still celebrated, at least in certain circles. Potsdamer Platz, Alexanderplatz, Anhalter Bahnhof, Bahnhof Zoo and Nollendorfplatz had a reputation as pleasure centres. From 1924, the economy buzzed for a short time, followed by a phase of relative economic stability which was later dubbed the "Golden Twenties". Beginning with the Great Depression in 1929, however, this temporary upswing came to a rapid end. The economic crisis that started with a crash on the New York Stock Exchange forced architects to build even more cost-effectively. Under these conditions, the guiding principles of urban development also continued to evolve. The period between 1924 and 1932 is therefore also regarded as the apex of New Building style, including five of Berlin's six UNESCO World Heritage residential estates.

Special places

Volksbühne at Rosa-Luxemburg-Platz

Cinema Babylon

Potsdamer Strasse, Nollendorfplatz and Alexanderplatz

Former Delphi cinema in Weissensee

Berlinische Galerie

1933 — The Nazi era begins

What should never have happened, did so in quick succession. Laws were suspended, while German businesses and cultural entities were either brought into line with the Nazi party line or liquidated. This, however, was only the beginning. As of 1933, many liberal and politically left-wing creative minds were banned from their professions, systematically ousted from their jobs and expelled. However, the situation was particularly dramatic for members of the Jewish community, from whence many important scientists and artists came. Some of them went into exile just in time, while many others were disenfranchised, deported or murdered. The Nazis needed only a few months to suspend important and fundamental rights. The new regime disempowered trade unions, local and state parliaments, and began to transform and Nazify all major companies by filling leading positions with sympathizers of Hitler and members of the National Socialist German Workers' Party (NSDAP). The terror reached a dramatic climax with the November pogroms of 1938, in which numerous synagogues and Jewish shops were destroyed. By invading Poland in September 1939, Nazi Germany triggered the Second World War, which cost the lives of an estimated 65 million people worldwide. From 1941 onwards, the systematic deportation and killing of Jews and other groups of victims began in Nazi-run concentration camps throughout Europe.

From 1940, the Allied forces launched bombing raids on Berlin. By the end of the war in May 1945, the Germans had murdered six million European Jews. Berlin lay almost completely in ruins, with vast swathes of residential, industrial and administrative buildings utterly destroyed. Miraculously, Berlin’s six World Heritage housing estates survived largely unscathed.

Special places

Holocaust Memorial

Reichstag

Olympic Stadium

Tempelhof Airport

1945 — Divided city

In response, the Allies launched the Berlin Airlift, during which food and other goods needed by the population were dropped over the city by air. Germany was quickly split into two countries. Pummelled by wartime bombs, Berlin lost its role as Germany’s capital but not its importance as a theatre of political competition. During West Germany’s currency reform, tensions mounted even further. They culminated in the foundation of two German states: East Berlin became the capital of the German Democratic Republic (GDR), while West Berlin was surrounded by the Soviet occupation zone, effectively turning into a political island within East German territory.

The seat of government for the newly founded Federal Republic of Germany (FRG) was Bonn, a comparatively small city in the west of the defeated country. The Berlin Wall was built in 1961 along the border to the Soviet sector and ran through the middle of Berlin. This barrier was so comprehensively secured that it sealed the division of the city, and would shape its fate for more than 28 years. On both sides of the Wall, the secret services of both political camps became active: on one side were Germany’s Bundesnachrichtendienst, America’s CIA, and Britain’s MI6, while the East German Stasi and Russian KGB were on the other. They all monitored not only enemy activities but also those of possible collaborators in their own countries.

East-West allegiances divided families, colleagues and friends, thus creating a climate of mistrust, especially in the East. Entering and leaving the GDR meant enduring strict border controls. After an escalation of peaceful protests in the GDR and a cautious thaw of restrictions under Soviet president Mikhail Gorbachev, the Wall suddenly fell in 1989 and another exciting chapter in the city's history began. Although some of the GDR’s key historic buildings have been razed, there are still physical signs of Cold-War-era division. This draws a great deal of interest from visitors who often ask whether they are currently in old East or West Berlin. Whether they’re native Berliners or outsiders who moved to the city long ago, residents take the old cross-border journey from Kreuzberg (in former West Berlin) to Mitte or Prenzlauer Berg (former East) in a more relaxed fashion.

Special places

Berlin Wall Memorial on Bernauer Strasse

Painted wall murals at the Eastside Gallery

Tränenpalast border crossing exhibition at S-Bahn station Friedrichstrasse

Bahnhof Zoo and City West area / America House

1957 — The two Berlins

In the East: The ‘workers' palaces’ of the GDR

Between 1950 and 1964, monumental apartment blocks were erected in the eastern sector along what is now Karl-Marx-Allee. Most of the buildings received the style that was typical during Josef Stalin’s reign in the Soviet Union. The buildings along the avenue cite historical elements, which is why experts call this style neo-classicism. They also aimed to demonstrate the quality of GDR architecture, and in particularly recall similar boulevards in eastern hubs such as Moscow, Leningrad, Kiev or Warsaw. At the same time, however, they also continued the tradition of Berlin buildings from the classicist period, a product of Prussian master builder Karl-Friedrich Schinkel. The monumental residential piles of the East were officially praised as "workers' palaces" – a designation that already suggests that they were in competition with the (capitalist) system.

From 1959, however, new buildings that rose further east were also slightly geared towards stylistic elements of Modernism, as they were also used in the West. In a later phase of construction, comparatively plain eight- to ten-storey buildings and several spectacular individual buildings emerged, including the cinemas International and Kosmos and the famous Café Moskau just outside Weberwiese underground station. The very wide avenue, which was designed to be suitable for military parades, is located in the districts of Friedrichshain and Mitte above the U5 underground line. From the east, it runs almost as straight as an arrow to Alexanderplatz, whose television tower marks the urban centre of former East Berlin from afar. Particularly striking are the tower buildings at Frankfurter Tor and Strausberger Platz, designed by the architect Hermann Henselmann.

In the West: The IBA in the Hansaviertel

The Hansaviertel (Hansa Quarter) formed a structural counterpoint to Karl-Marx-Allee. Built in 1957 as a direct response to the building activities in the East, it consists of several high-rise buildings and large apartment blocks in a modern, late-1950s style. The first and tallest building in the quarter is the Giraffe, thus named for its colourful balconies that allowed residents to peer over the Wall. In general, people wanted to live high up. The high-rises are loosely integrated into the design of the Tiergarten park. A residential quarter for wealthy Berliners had emerged here at the end of the 19th century, but was completely destroyed in the Second World War. The construction of the new Hansa Quarter was consciously a political statement. It took place within the framework of the International Building Exhibition (IBA or Interbau for short) in 1957, to which, in addition to a number of German architects, several influential and internationally renowned architects were invited. Each of them submitted one house design to the IBA.

Occasionally, there were transnational cooperations in the design of the open space facilities. By using this procedure, West Germany wanted to demonstrate its new cosmopolitanism in a media-friendly and widely visible fashion. At the same time, they were seeking to rejoin the international community of architectural modernity, and to re-assume the special position Germany's building avant-garde held before the Nazis came to power – but in a politically and diplomatically correct manner. With its special combination of residential construction and green spaces, the urban development concept of the Hansa Quarter, embedded in the park landscape, connected nicely with Berlin’s World Heritage housing estates, which under the slogan "light, air and sun" were built for everyone starting in 1913. Under the title "The two Berlins", the city is currently campaigning for the erstwhile competing quarters to be jointly nominated for inclusion as UNESCO World Heritage sites.

Special places

Large city model in the Haus am Köllnischen Park

Strausberger Platz (via underground line 5)

Frankfurter Tor (via underground line 5)

Buildings around the Hansaplatz underground station

Academy of Arts on Hanseatenweg

Corbusier House near the Olympic Stadium

Overview provided by:

Berliner Forum für Geschichte und Gegenwart e.V., Ben Buschfeld