Biographies

of planers, tenants and related protagonists

Born in 1885 in Königsburg, East Prussia (today Kaliningrad), Wagner was an outstanding political organizer and networker. Along with Bruno Taut, who also came from Königsburg, Wagner is considered the second key figure in the construction of Berlin’s housing estates. From 1905 to 1910 he studied architecture, urban planning and economics. In 1911, he became head of the building construction office in the town of Rüstringen (now part of Wilhelmshaven), a position he held for almost four years. In 1915, he received his doctorate in Berlin. The dedicated Social Democrat was appointed municipal planner for Berlin-Schöneberg in 1918 and quickly made a name for himself with the Lindenhof housing estate, which he planned with Leberecht Migge and Bruno Taut. A political mastermind with great foresight, Wagner created the logistical and political foundations of the New Building movement in Berlin. He was a co-founder of the architecture magazine Deutsche Bauhütte, initiated the founding of housing company GEHAG and acted as managing director of various influential associations. As the second architect of the Horseshoe Estate, where he was initially responsible for designing the row of houses on Stavenhagener Strasse, Wagner was appointed in 1926 as building director for Greater Berlin, an amalgamation of municipalities created in 1920. In this role he initiated and participated in many key projects for the up-and-coming metropolis. Apart from the construction of housing estates, these projects included the expansion of the underground railway network, the rebuilding of Alexanderplatz, the design of Wannsee beach and of Charlottenburg’s exhibition grounds. In 1933 Wagner went into exile under pressure from the National Socialists, first to Turkey than to the United States in 1938. A year later he became a professor of urban planning at Harvard University.

Born in 1880 in Königsburg, East Prussia (today Kaliningrad), Taut designed four of Berlin’s six World Heritage residential estates: Falkenberg Garden City, the Schillerpark Estate, the Horseshoe Estate and the Carl Legien Housing Estate. In 1909 he founded the architectural practice Taut & Hoffmann, which was joined in 1912 by his younger brother Max. The elder Taut became known not only for Falkenberg, but above all for the glass industry pavilion at the craftsmen’s association Deutscher Werkbund’s premiere exhibition in Cologne in 1914. After the First World War, he worked from 1921 to 1924 as a municipal building surveyor in Magdeburg. In 1924, Taut returned to Berlin and was appointed chief architect of the newly founded housing association GEHAG. In this role, he decisively shaped the face of New Building and Berlin public housing in the years that followed. A total of around 134,000 apartments were built under his management. His main works include the Horseshoe Estate and the Onkel-Toms-Hütte housing estate in the Berlin-Zehlendorf district. In addition to his practical work, Taut wrote a book of architectural theory, two utopian illustrated books and several other influential publications and appeals. Taut understood like no-one else how to use details and colours in architecture in such a way to prevent affordable mass housing from becoming monotonous. In 1930, Taut became a professor at Berlin’s Technical University (now TU Berlin) and joined influential associations such as the Workers’ Council for Art, the Deutscher Werkbund and the Ring of Ten architectural collective. Persecuted by the National Socialists as a “cultural bolshevist”, Taut went into exile in 1933. Although he worked mainly in Japan as a journalist, he was able to complete several prominent buildings in Turkey after 1936. He died from an asthma attack at the age of 58 in his house in Istanbul.

Lesser was born in Berlin in 1869 and ran a small design and planning office beginning in 1909, making him the first independent landscape architect in Germany to work exclusively in planning. In addition to the green and open spaces of Falkenberg Garden City and White City, Lesser designed many important facilities in and around Berlin. His designs ranged from small-scale, house and villa gardens to cemeteries and entire housing estates. Among his most famous works are the green spaces of Berlin’s district of Frohnau (a one-time garden city), and the blueprint of the country home community Bad Saarow-Pieskow on the lake Scharmützelsee, which was popular with film actors and artists in the 1920s. From day one, his commitment to social issues and journalism made Lesser an opinion leader. He published a garden calendar, became a lecturer, gave speeches, joined the craftsmen’s association Deutscher Werkbund among other professional organisations, and wrote a number of articles and books. Particularly noteworthy is the book Volksparke heute und morgen (People’s Parks Past and Present) which made an last impression on the reform movement in 1927. A pioneer of broadcasting, from 1925 to 1933 he presented a popular gardening programme for the radio station Funkstunde. In 1919, he was appointed to the presidium of the German Garden City Society and served as its president from 1923 until 1933, when he was removed from all offices due to his Jewish origins. In 1939 he emigrated to Sweden, where he lived until his death.

Considered one of the most important garden architects of the 20th century, Migge was born in Gdansk in 1881. After taking an apprenticeship in horticulture, from 1904 he worked as artistic director of a large Hamburg landscaping company. From 1913 he committed himself to kitchen gardens and acted as a pioneer of social and nature-oriented garden design. Migge published several books, was a member of the craftsmen’s association Deutscher Werkbund and editor of the newspaper Siedlungswirtschaft. After spending several years in the artists’ colony Worpswede near Bremen, he moved to Berlin, where he worked as an independent landscape architect in close collaboration with Martin Wagner and Bruno Taut, among others. In addition to the Horseshoe Estate, Migge was also in charge of the open space planning on the Siemensstadt estate, the Onkel-Toms-Hütte housing estate in Berlin-Zehlendorf, and on the Römerstadt estate in Frankfurt am Main, which was built under the direction of local city planning officer Ernst May. Unlike most of his New Building colleagues and companions, Migge sympathized with National Socialism in the early 1930s, but remained suspicious of the new government and increasingly withdrew to his self-sufficiency project on Sun Island in Lake Seddin. He died of kidney disease in 1935.

Hillinger was born in 1895 in Nagyvárad, Hungary. Barred from studying in his native country as the son of Jewish parents, he moved to Berlin in 1919 and enrolled in architecture at the city’s technical university. In 1924, Hillinger was appointed head of the design office at the GEHAG housing association. He worked closely with GEHAG’s chief architect, Bruno Taut, and was a key designer of the Carl Legien estate. Most likely, he was deeply involved in the design of the housing company’s mass-produced components. These included idiosyncratic window, entrance and staircase details, as well as the model kitchen created around 1926 for the Onkel-Toms-Hütte residential estate. In 1933, the left-leaning GEHAG aligned with Nazi policies and Hillinger was forced to give up his position. He then focused on designs for private clients. In 1937, Hillinger emigrated to Turkey, as had Martin Wagner and Bruno Taut before him, and worked under Kemal Atatürk’s reform-minded government as a designing architect for the culture ministry and as a university lecturer. From 1940 to 1943 he headed the architecture school in Ankara. In the early 1950s, Hillinger emigrated with his family to the United States, where he died in New York in 1973.

Salvisberg was born in Switzerland in 1882. After studying at the technical college in Biel, he worked mainly in Germany until 1929. Following stints in Munich and Karlsruhe, where he gave guest lectures at the technical universities, he moved to Berlin in 1908 and founded his own architectural practice in the capital in 1913. His most famous works include the expansion of the garden city of Piesteritz near Wittenberg, the Forest Estate “Onkel-Toms-Hütte” in Zehlendorf and the White City Estate in Reinickendorf. In addition to housing estates, Salvisberg designed several villas and private homes as well as hospitals and institutional buildings. Although he created important works of Modernism, it is difficult to define his work in any single style. In October 1928, he was appointed design professor at the renowned Swiss Federal Institute of Technology in Zurich. Besides that he also acted as chief architect for the Basel-based pharmaceutical company Hoffmann-LaRoche.

Born in 1850, Ahrends grew up in affluent circumstances at a villa on the Wannsee near Berlin. Like his siblings, he converted from Judaism to Christianity and changed his name, from Arons to Ahrends. Despite this assimilation, he was denied his original wish to study shipbuilding because of his Jewish origins. Instead, Ahrends studied architecture at technical universities in Munich and Berlin-Charlottenburg. Among his most important works are several residential buildings and housing estates in Berlin, as well as several villas and country houses. His house on Berlin’s Miquelstrasse, which was built for his own family, later became the official villa of the Bundestag president. After the National Socialists banned him from working in 1937, Ahrends fled to Italy and then to Britain, where he was eventually detained as an enemy alien despite his Jewish roots. In 1948, he died shortly after emigrating to Cape Town, South Africa.

Büning was born into a textile manufacturing family in Borken, Westphalia, in 1881. He studied architecture at technical universities in Munich, Dresden and Berlin-Charlottenburg. In 1909, he founded his own architecture practice in the German capital. Büning rose to prominence as an architect and university lecturer. As the latter, he believed that talented students should be allowed to study without first obtaining their school-leaving certificate. He also pushed for craftsmanship skills to be united in the execution of architecture and construction, disciplines that Büning believed constitute the true quality of the building trade. In 1928, he published his Bauanatomie (The Anatomics of Building), a standard work on the subject in which he opposed a one-sided focus on style matters.

Scharoun was born in Bremen in 1893. After studying at Berlin Technical University, he worked as a freelance architect from 1919 to 1925. From 1925 to 1933, he was a professor at the Academy of Art in Breslau (Wroclaw in present-day Poland). Scharoun enjoyed world renown for his design of the Siemensstadt estate. Like his colleague Hugo Häring, he is considered an advocate of “organic construction”. Despite external forms that are often strikingly concise, his structures are not a stylistic end in themselves. Many of his famous buildings and floor plans are, in fact, highly functional and derive their quality from a conscious departure from boxy design principles. The National Socialists regarded Scharoun, like many other leading architects of the era, as an enemy. He was thus denied public contracts in Germany but remained to build mainly private residences. One of his most notable is the factory-owner’s villa Haus Schmincke in Löbau, Saxony. Scharoun worked as a Berlin city planner in 1945-46 and together with other architects, he presented a radical concept for the post-war reconstruction of Berlin. From 1956 to 1961, he implemented elements of this concept in the Charlottenburg North housing estate near Siemensstadt. Completed in 1963, the Berliner Philharmonie concert hall at the Kulturforum near Potsdamer Platz is considered his crowning achievement. Sharoun was one of the very few public housing architects to live in buildings they designed themselves.

Considered one of the most influential pioneers of Modernism, Gropius was born in Berlin in 1883. He came from an upper-middle-class background and was a great-nephew of the architect Martin Gropius. The young Gropius began his studies in 1903 at Munich’s technical university but three years later, switched to the technical university in Berlin-Charlottenburg. In 1908, he broke off his studies to work at Peter Behrens’ architecture practice. Many architects who worked in that office would become famous as pioneers of Modernist architecture, including Ludwig Mies van der Rohe and Le Corbusier. Gropius had many contacts through his membership of the craftsmen’s association Deutscher Werkbund and the Workers’ Art Council. His first major work was the Fagus Factory, built in 1912 near Hildesheim in Alfeld, Lower Saxony, which is regarded as one of the first examples of New Building style. During the First World War, Gropius served as a non-commissioned officer for four years. In 1919, he founded the Bauhaus design school in Weimar and served as its director until 1926. The designs for its famous university building and the Masters’ Houses in Dessau, the second home of the Bauhaus school, date from this era. Today these buildings are part of the UNESCO World Heritage Site, as are the Fagus Factory and the Siemensstadt estate. From 1925, Gropius became involved in mass housing construction. In 1934 he emigrated first to Britain, then in 1937 to the United States, where he taught at Harvard University. In 1948, Gropius and some younger Boston architects founded The Architects Collaborative (TAC). Later, he frequently returned to Berlin to work on projects such as his building in the Hansa Quarter, which was erected for the International Building Exhibition of 1957, or on Gropiusstadt in southern Neukölln, a residential estate based on an urban design by TAC.

Bartning was born in Karlsruhe in 1883. After taking his school-leaving exam in 1902, he began to study architecture at the technical university in Charlottenburg. He took a trip around the world in 1904 and continued his studies but did not complete them properly, due to unknown reasons. By the outbreak of the First World War in 1914, Bartning had already built 18 churches in Germany. In 1918, he became a member of the Workers’ Art Council, the forerunner of the architects’ association The Ring. Presented in 1922, his spectacular design of an Expressionist church, the Sternkirche, was never realised. Bartning became famous for a steel church built in Cologne in 1928. Besides houses of worship, he also designed clinics, residences, factory buildings and housing estates such as Siemensstadt. His name is synonymous with the reconstruction of the North Sea archipelago Helgoland. Bartning was honoured upon his death in Darmstadt in 1959.

Forbat was born in 1897 in Pecs, Hungary. After he finished his architecture studies in Munich, the Bavarian government tried to deport him as an undesirable foreigner. However, Walter Gropius gave the talented young man a job in his Weimar studio and had him plan a “Bauhaus estate”. It was never realised, but aspects of its blueprint flowed into the construction of Haus am Horn, a home in Weimar. In 1928 Forbat became a German citizen, founded his own architecture practice and was well on his way to becoming a star architect. Martin Wagner, Berlin’s planning councillor, entrusted Forbat with the construction of 1,200 apartments in the governmental research estate Spandau-Haselhorst, among other commissions. To escape the growing anti-Semitism in Germany, Forbat, a Jew, went to the Soviet Union in 1932 to work for the state urban planning organization Standardgorprojekt. Completely disillusioned after a few months, he was unable to return to Germany after the National Socialists came to power. Forbat was also subject to anti-Semitic attacks in Hungary. After an attempt to bring him to the United States as a university lecturer failed, Sweden offered Forbat his only avenue of escape. He died in 1972 in Stockholm, where he is still honoured as an excellent urban planner.

Häring was born in 1882 in Biberach, Swabia in southwestern Germany. He studied at the technical universities in Stuttgart and Dresden. In 1903, he completed his studies under Theodor Fischer, the first chairman of the craftsmen’s association Deutscher Werkbund. Häring then worked as a freelance architect in Hamburg and East Prussia. During the First World War, he was employed as an interpreter. In 1921 he moved to Berlin, where he shared a study with Ludwig Mies van der Rohe. In 1923-24, the pair founded the Ring of Ten in Berlin, which would later become the architectural association The Ring and extend beyond the German capital. In 1926, Häring was appointed secretary of The Ring, which by now had 27 members. While Walter Gropius and Mies van der Rohe stood for a technical-industrial style of architecture, Häring, like his colleague Hans Scharoun, represented “organic architecture”. His main works include the residential buildings on the Onkel-Toms-Hütte estate in Berlin-Zehlendorf (1926-27) and his rows of flats in Siemensstadt (1929-30). Häring was one of the few leading architects who did not flee Germany during the Nazi era, opting to run a private school for design beginning in 1935. After the school was bombed during the war, he returned to his home town of Biberach in 1944. From 1947 to 1950, Häring served on the staff of Berlin’s Institute for Construction at the Academy of Sciences, headed by Hans Scharoun. Häring died in Göppingen in 1958.

Henning was born in Berlin in 1886. In 1916, he moved to Zurich, where he came into contact with the avant-garde artist group Dada and worked as a sculptor in the Expressionist style. In 1919, he joined the revolutionary Workers’ Art Council, whose members included Bruno Taut and Walter Gropius. Henning was an advocate of the New Building style and designed large residential projects in Berlin, including the Baumschulenweg estate in Treptow-Köpenick and the Metastrasse estate in Lichtenberg. His most famous buildings include the Mosse publishing house in Berlin’s central Mitte district, which he planned to rebuild in 1921-23 together with Erich Mendelssohn and Richard Neutra. After 1933, Henning remained in Germany but was allowed to build in his preferred New Objectivity style only for industrial construction. In his other works, he adapted to the architectural style of the Nazi regime. After 1945, Henning returned to Modernist design principles in his work.

Born in 1876 in Rostock, Tessenow is known as a pioneer of reform-oriented construction in Germany. The son of a carpentry contractor and a student of architecture, Tessenow knew how to combine practical and artistic considerations. He built, taught and published, especially in the area of small residential construction. In 1909, Tessenow moved to Dresden to take up an assistant’s position at the city’s university. From 1909 to 1913, he helped to construct the first German garden city in Hellerau near Dresden. The residences he planned there and his later design of the Hellerau Festival Theatre made him famous. Hellerau was a showcase project of life-reformist architecture, as was the estate in Falkenberg Garden City. Tessenow designed the only building in Falkenberg that Bruno Taut did not, teaching in Vienna during the First World War and returning to Hellerau in 1919. From there he moved to Berlin in 1926 to teach at Charlottenburg’s technical university. In 1931, Tessenow won a prestigious competition for his redesign of the New Guardhouse. In 1941, he was forced to retire and moved to the north German state of Mecklenburg. Shortly after the Second World War, he accepted an offer to work in Turkey but returned to his chair in Berlin in 1947. Tessenow died in West Berlin in 1950.

Taut was born in 1884 in Königsberg (now Kaliningrad) in East Prussia and like his elder brother Bruno, was one of the leading lights of Classical Modernism. Both brothers worked together in the architecture practice Taut & Hoffmann from 1912 onwards, but kept their building tasks strictly separate. While Bruno specialized in housing estates and large residential complexes, Max planned mainly school and administration buildings. His best-known structures in Berlin are the headquarters of the German Printers Association, a school named after him in the Lichtenberg district and the Consumers’ Cooperative department store on Oranienplatz in Kreuzberg. He also designed several detached summer houses on the coastal island of Hiddensee. Max did not go into exile and shortly after the war, resumed his work as an architect, university lecturer and urban planner. During his post-war reconstruction work in Berlin, Max planned minor extensions to the Schillerpark Estate that had been planned by his brother Bruno, who died in exile in 1938. Max also worked on the surroundings of the Horseshoe Estate.

Rossow was born in 1910 in the Berlin district of Rixdorf, which was later renamed Neukölln to shed the former’s infamous reputation as a nightclub quarter. In 1926, Rossow began an apprenticeship as a gardener and passed his exam as a garden technician in 1932. A year later, he was hired by the office of garden technician Martha Willings, where he soon became a partner and from 1940 held the job of managing director. After the Second World War, Rossow was put in charge of green spaces to be created in the American sector. In 1948, he became a lecturer at the Berlin College of Fine Arts. Regarded as one of the most important landscape architects of the 1950s to 1970s, Rossow worked closely with Hans Scharoun and Egon Eiermann. In the early 1950s, Hans Hoffmann designed extensions to the Schillerpark Estate. Within this framework, Rossow planned and revised the greenery and open spaces of Schillerpark, including the park and the adjacent housing estate. Rossow’s most famous works include the greens of the Academy of the Arts in Berlin’s Hansa Quarter and in the Tiergarten, whose reconstruction he managed in 1950-51. From 1966 to 1975, he headed the Institute for Landscape Planning at the University of Stuttgart, and from 1976 he oversaw the Department of Architecture at the Academy of Arts in Berlin. Rossow died in 1991 in Berlin.

was born in Berlin in 1904. After studying architecture, he joined the studio Taut & Hoffmann at the end of the 1920s. In the course of this collaboration with Bruno Taut, he was involved in various modern residential projects. His best-known works include the 1954-58 extensions to the Schillerpark Estate, which, by incorporating generously glazed loggias, living spaces and staircases, bridge the gap between the classic modernism of the 1920s and typical stylistic elements of the 1950s. The name “Glass-Hoffmann” quickly developed, which on the one hand refers to his most typical design feature, but at the same time distinguishes him from a Swiss colleague of the same name. Hoffmann later worked as an architect for the building and housing cooperative “1892eG”, where he was also member of the board. In addition to the Schillerpark estate, he also created extensions for the Attillahöhe estate in Tempelhof, several residential buildings in Berlin and was also involved in the planning of the Charlottenburg-Nord residential area, which adjoins the Siemensstadt ring estate. In the context of the World Heritage Site, however, his delicately constructed “flower windows” in Schillerpark, are particularly noteworthy, because they serve as a climatic intermediate level and were thus part of an innovative energy management system which was further enhanced in the course of the restoration work.

Born in Hamburg in 1868, Behrens is considered an important pioneer of modern industrial and graphic design. He started out as an artist, studying painting at the art academies of Karlsruhe, Düsseldorf and finally in Munich, where he co-founded various artists’ associations. In the years that followed, he became involved in the applied arts, although this discipline did not formally exist at that time. In 1899, Behrens was appointed to the Darmstadt-Mathildenhöhe artists’ colony, a model in the spirit of the Art Nouveau and Reform movements that aimed to demonstrate an exemplary collaboration between arts and crafts. Behrens created a landmark in the form of his private residence in Darmstadt, for which he also designed the entire interior. In 1903, at the age of 34, he was appointed director of the Düsseldorf School of Applied Arts, a position he held until 1907. The same year, Behrens became a co-founder of the craftsmen’s association Deutscher Werkbund, and moved to Berlin to set up his own architectural practice. The office worked with holistic methods and developed into an important training ground for Modernism. Its staff included the architects Walter Gropius, Ludwig Mies van der Rohe and Le Corbusier before they became famous. Also in 1907, Peter Behrens was appointed artistic director by German electrical goods maker AEG, whose image he would help to shape in the years that followed. At AEG, Behrens designed not only numerous industrial and administrative buildings, but also household appliances, logos, advertising graphics and typefaces. He is considered a pioneer of modern graphic design. In 1921, Behrens was appointed to the Düsseldorf Art Academy. A year later, he was named head of the Master School of Architecture at the Academy of Fine Arts in Vienna. From 1936, he held a similar post at the Academy of Arts in Berlin, where he died from heart failure in 1940.

May was born in 1886 in Frankfurt am Main. After studying architecture in London, Darmstadt and Munich, he became an intern for Sir Raymond Unwin in 1910, where he worked on the Hampstead Garden Suburb in north London. May translated Unwin’s work on the concept of satellite towns into German. After serving in the German military in World War I, May planned residential estates in Breslau (today Wroclaw, Poland) and the Silesia region, incorporating the satellite city concept. In 1925, he was appointed Frankfurt’s planning commissioner and headed the city’s “New Frankfurt” housing construction programme. By the time the project was discontinued in 1929-30 due to the world economic crisis, more than 20 housing estates with some 15,000 flats had been built during his tenure. May’s role in Frankfurt was as important as that in Berlin of Martin Wagner and Bruno Taut, both of whom were May’s colleagues at the craftsmen’s association Deutscher Werkbund. The Frankfurt Kitchen, a forerunner of the modern fitted kitchen, was designed by Margarete Schütte-Lihotzky during the New Frankfurt programme. In 1930, May was appointed to run Russia’s national building authority with 800 employees. As head of the so-called “May Brigade”, he planned a spate of new housing estates in Russia based on row construction. May was ultimately responsible for the planning of over one million apartments in the country’s new industrial cities such as Magnitogorsk, Leninsk and Kuznetsk. However, May chose not to conform to Stalin’s ideas of Socialist Classicism and ended his contract prematurely in 1933. The architect could not return to National Socialist Germany, however, moving instead to Kenya, where he worked first as a farmer and later as an architect and urban planner. May, who died in Hamburg in 1970, is recognized as one of the few major players in New Building and was heavily involved in Germany’s post-war urban development. Well-known housing estates from this period include May’s New Altona in Hamburg and his New Vahr in Bremen.

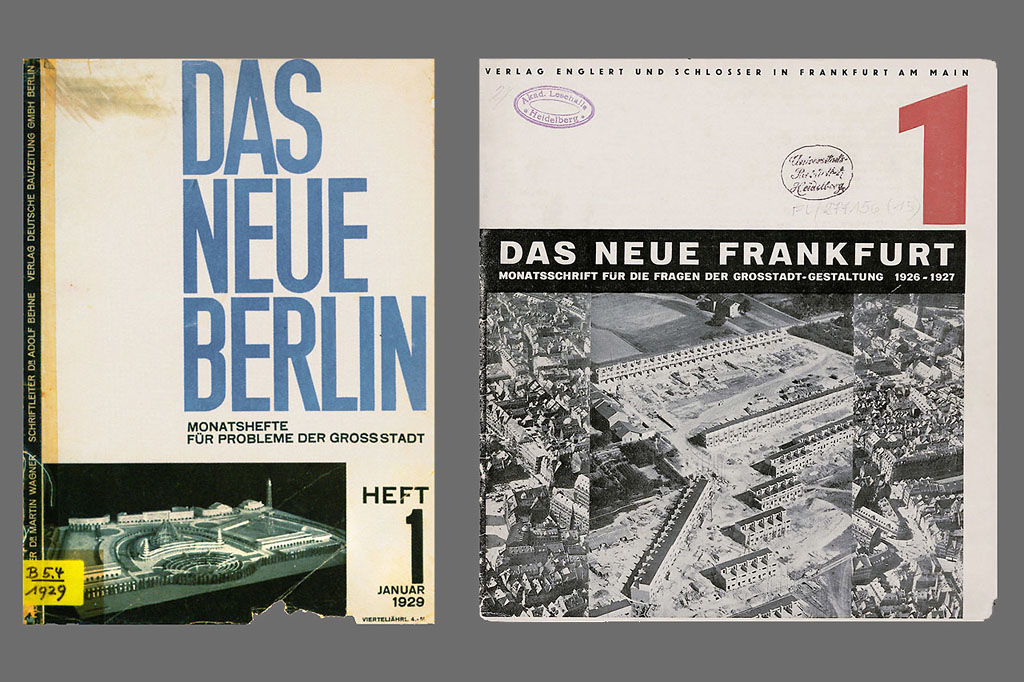

Covers of the monthlies Das Neue Berlin and Neues Frankfurt.

Sources: Berlin Senate Department for Urban Development and Housing (left) and digi.ub.uni-heidelberg.de/diglit/neue_frankfurt1926_1927/0001 (right).

Otto was born in Berlin in 1872. Besides his professional activities as a businessman in printing and publishing houses, he became interested in emerging ideas of the life reform movement. Otto was a staunch supporter of the social-ethical and economic reforms of the garden city movement and maintained close ties to the Friedrichshagen circle of poets. Together with like-minded spirits such as Bernhard Kampffmeyer and Robert Tautz, in 1902 Otto founded the German Garden City Society DGG in Berlin, where he held the position of general secretary and administrator for many years. As a founding member, he paved the way for the DGG’s only Berlin project, Falkenberg Garden City, and supported the estate as a long-standing representative on the Alt-Glienicke municipal council. The Otto family’s residence at Am Falkenberg 119 was designed by Heinrich Tessenow and served as DGG’s office. After the National Socialists came to power in 1933, the estates expert was stripped of all his offices and forced to emigrate. His travels took him via England to France, where he continued to work on housing projects. In 1942, Otto was forced to return to Berlin, where he died in 1943.

Tautz was a reformer, publishing manager, printer and journalist born in 1871. He maintained close and friendly ties with the Friedrichhagen circle of poets including Paul Kampffmeyer and Erich Mühsam, the latter becoming a resident of the Horseshoe Estate. These men shared Tautz’s sense of community culture. Together with Adolf Otto, Tautz was involved in the founding of the German Garden City Society DGG and the non-profit building cooperative Gartenvorstadt Gross-Berlin (Greater Berlin Garden Suburb). He also actively supported the construction of the Falkenberg estate and was one of its first residents. Robert Tautz lived together with his wife and seven children at Akazienhof 25. In the 1920s, he enlivened the community by publishing the estate newspaper Der Falkenberg and was a key organiser of Falkenberg’s summer festivals.

Brought up in a middle-class Jewish family, Mühsam was a renowned anarchist, author and publisher. Shortly before his exams at secondary school, he was expelled for “social democratic activities” and worked as an author and satirist. After a few years travelling around Germany, he moved to Munich and founded several anarchist groups. Among other publications, Mühsam wrote for the satirical magazine Simplicissimus and became a pivotal figure in the declaration of Munich’s short-lived Soviet Republic, earning him a 15-year prison sentence. After his early release he moved with his wife, Zenzi, to 48 Dörchläuchtingstrasse in Berlin’s Horseshoe Estate, where he published the journal Fanal. Mühsam was also notorious in the neighborhood for his free lifestyle, but he got involved by being an active member of the tenants’ council, for example. Mühsam maintained a lively exchange with the publicist Rudolf Rocker, who lived just a few streets away, as well as with other prominent residents such as the artists Heinrich Vogeler and Stanislav Kubicki and the publicist Leon Hirsch. After the National Socialists came to power, Mühsam was arrested in the Hufeisensiedlung in 1933 and (despite the protests organized by Zenzi Mühsam) hanged in the Oranienburg concentration camp a year later – staged as a suicide by the SS. A memorial stone on site commemorates the famous resident.

Vogeler was the best-known artist amongst the residents of the estate. The multi-talented artist worked as a painter, graphic artist, architect, writer and teacher. He grew up in a middle-class family and enrolled in 1890 at the Art Academy in Düsseldorf, switching to the influential North German artists’ colony of Worpswede in 1894. As a graphic artist and illustrator he became a leading proponent of Art Nouveau style. In Worpswede, Vogeler designed his house as a “complete work of art” and experimented with growing his own garden food. He was in touch with other famous artists and residents in the colony, including landscape architect Leberecht Migge, and was a founding member of the craftsmen’s association Deutscher Werkbund. After the First World War, he became a vocal supporter of utopian pacifism and was persecuted by the Nazis. Vogeler often travelled to the Soviet Union, where he was active in politics and teaching. Between 1927 and 1931 Vogeler lived with his family at 138 Onkel-Bräsig-Strasse in Berlin.

Legien was born in the West Prussian town of Marienburg (Malbork in present-day Poland). He was an important trade union official for whom the Carl Legien Housing Estate in Prenzlauer Berg is named. After the early death of his parents, Legien grew up in an orphanage. In 1875 he began an apprenticeship as a wood turner, which he completed in 1880. He then worked as a journeyman in Berlin, Frankfurt am Main, the Cologne area and finally in Hamburg. In 1885, Legien joined the Social Democratic Party. A year later he joined the woodturners’ guild and its associated trade union in Hamburg, and got involved in the trade union movement. After serving for several years as its secretary, in 1913 Legien became president of the International Trade Union Confederation. In 1919, he was elected president of the General German Trade Union Federation ADGB. Towards the end of the First World War, Legien participated in labour negotiations with industry. As a result of these talks, the trade unions were recognized as official representatives of the workers’ interests and a standard eight-hour workday was introduced. The Carl Legien Housing Estate, a vocational school in Neukölln and the thoroughfare Legiendamm in Kreuzberg are among the projects that bear his name. Legien died in Berlin in 1920.

Weinert was a communist and anti-fascist writer, painter and caricaturist who lived in Falkenberg Garden City, and for whom the central axis on the Carl Legien Housing Estate was named. Born in Magdeburg in 1890, he started out in locomotive construction. After his apprenticeship between 1905 and 1908, Weinert was drawn to study art, attending art academies in Berlin and Magdeburg. He then worked as a book illustrator. After serving in the First World War, Weinert became a drawing instructor, actor and at times unemployed. Beginning in 1921, he began to make a name for himself in cabaret and published his first satirical poems and articles in left-wing newspapers and magazines. Weinert was a committed communist and a popular speaker at German Communist Party events. Persecuted by the Nazis, he was forced to emigrate in 1933. Weinert then served as a Brigadist in the Spanish Civil War and as a translator in Moscow. After the Second World War, he returned to East Berlin in 1946, where he became an administrating vice president of education and the head of art and literature for the new German Democratic Republic, where he helped develop the regime’s cultural policy. Weinert died of pulmonary tuberculosis in Berlin in 1953.

Reuter’s name appears on streets in the Large Housing Estate Britz, part of which is known as Fritz-Reuter-Stadt. This area includes the Horseshoe Estate and the neighbouring Krugpfuhl Estate. Reuter was one of Germany’s most popular poets and novelists. Born in Stavenhagen in 1810, he wrote in Low German dialect. Throughout his life, this critical free spirit sought out “ordinary” people and made them the protagonists of his works. Many of these figures – such as Onkel (Uncle) Bräsig, Jochen Nüssler and his daughters Lining and Mining – have streets named after them today. The street Lowise-Reuter-Ring is named after Reuter’s wife Luise, while Onkel-Herse-Strasse refers to a teacher from Reuter’s schooldays. Street names containing Parchim, Stavenhagen, Gielow and Talberg all relate to particular stations in Reuter’s life. The street name Dörchläuchting is Low German dialect for “Your Highness” and cites a character in a Reuter novel. “Hüsing” describes the social norms of the estate, namely the right of domicile granted by feudal lords to small farmers. In Low German, Hüsing generally means “domestic security”.