GEHAG > privatisation

The privatisation of Berlin municipal housing company GEHAG reads like an economic crime thriller. The 1998 sell-off seems all the more surprising today, given the capital's tight housing market and rapidly rising rents. GEHAG was founded to build affordable housing for the lower and middle classes, and this pledge shaped its culture and corporate policy. But the Berlin government, led by the Social Democrats, nonetheless decided to sell GEHAG and its holdings of prestigious monuments to ease the city's beleaguered finances. The company was sold by auction and the procedure was subject to a number of legal conditions; bidders who were deemed unsuitable were excluded in advance. The contract was awarded to a relatively small property company, RSE Grundbesitz und Beteiligungs-GmbH, which grew out of the railway builder and operator Rinteln Stadthagener Eisenbahn AG. The latter had a tradition of building housing estates for its plant workers.

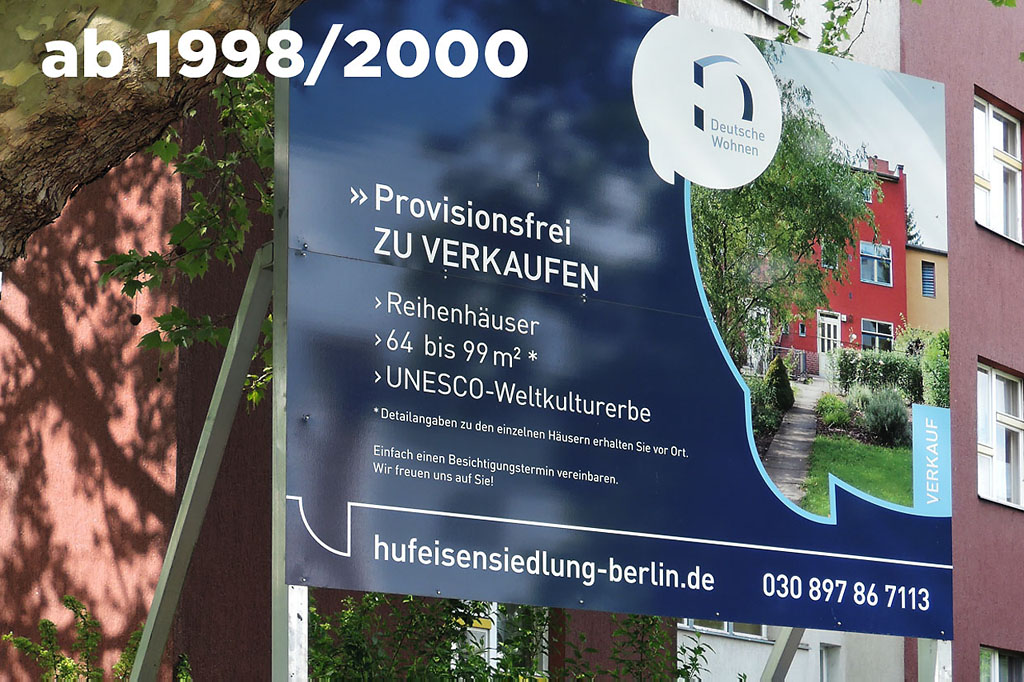

The selling price for GEHAG's properties was around €1,000 per square metre, extremely cheap by today's standards (current market prices are around €5,000 per square metre). Shortly thereafter, however, RSE was taken over by Hamburg-based WCM Immobilien-Holding, a property company that had been excluded from bidding. In quick succession, there were several takeovers of GEHAG’s favourably priced portfolio on the stock market, and properties designed by Bruno Taut in the Horseshoe Estate briefly appeared in the portfolios of US hedge funds such as Oaktree Capital Management and Blackstone Capital. In the course of their ownership changes, these properties – comprising nearly 700 terraced houses, which up to that point had been leased – were gradually sold off to individual private owners, a policy maintained today by Deutsche Wohnen, the last major buyer of Horseshoe Estate properties. This now means that the Horseshoe Estate has one large proprietor (Deutsche Wohnen still owns 1,263 apartments there) and well over 600 individual private owners. This fragmentation has made it much more difficult to uniformly preserve the finely tuned World Heritage Site, leading residents to develop their own private projects. These include the Infostation in the Horseshoe Estate and a large, web-based database dedicated to the preservation of the estate.