Falkenberg Garden City (1913–16)

The origins

Facts and Figures

- Location: District of Treptow-Köpenick, locality Bohnsdorf

- Public transport: S Grünau

- Total area of world heritage: 4.4 hectares

- Total area of buffer zone: 10.9 hectares

- Number of apartments: 128, of which 80 are single-family houses (mostly in rows or as semi-detached houses) and 48 are floor apartments in six buildings

- Apartment sizes: one to 5 rooms

- Construction period: 1913–16

- Urban design: Bruno Taut

- Architects: Bruno Taut and Heinrich Tessenow (single-family homes)

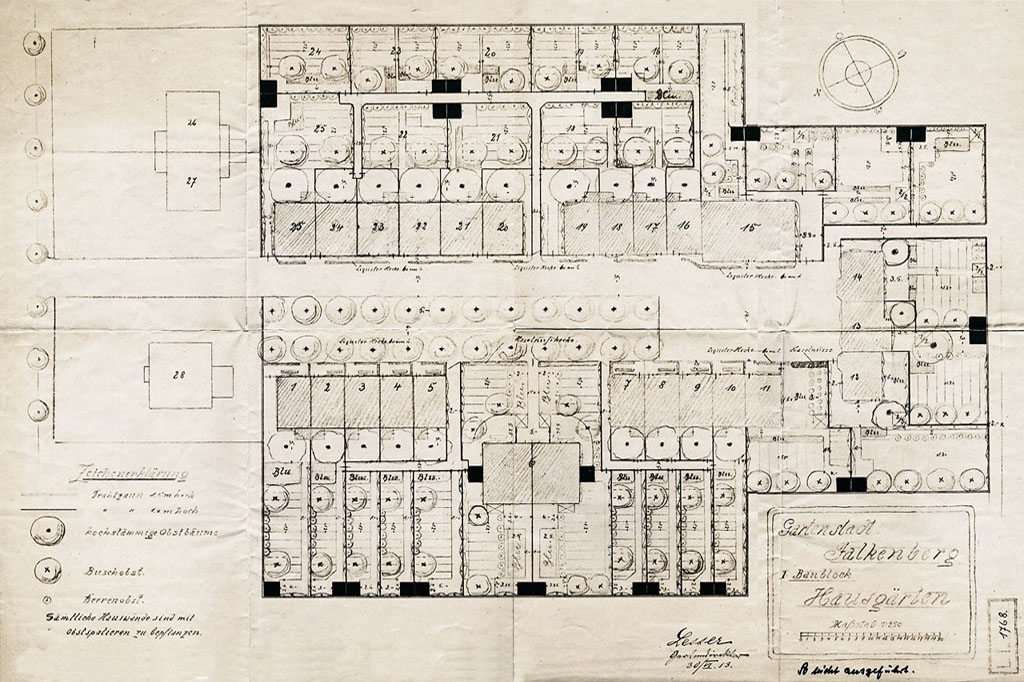

- Landscape architect: Ludwig Lesser

- Developer: Gemeinnützige Baugenossenschaft Gartenvorstadt Groß-Berlin GmbH

- Owner: Berliner Bau- und Wohnungsgenossenschaft von 1892eG

- Residents (approx.): 230

- Tenants: 740

- Monumental category: Ensemble-Monument and Garden-Monument

Message

"The housing question is one of the most burning economic issues at present. This is not surprising when you consider that the average rent for a room in Berlin’s nicer districts is currently 300 marks (...) Rents are not much lower in other big cities, either.”

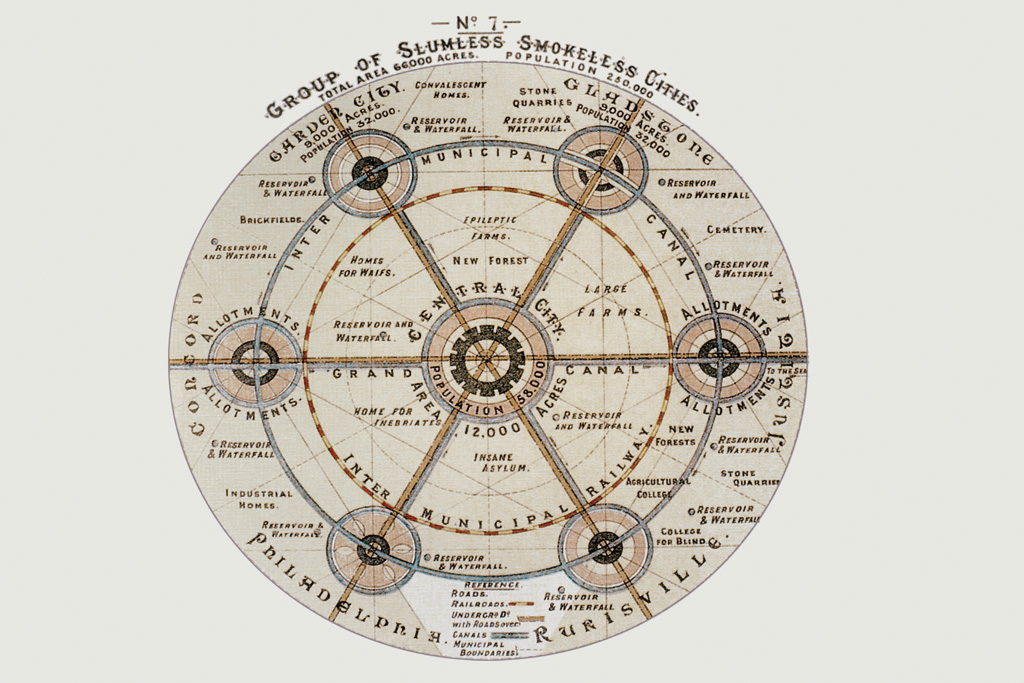

These statements, still topical today, were taken from a 1907 publication by the German Garden City Society DGG. Big cities such as Berlin and London were bursting at the seams due to ongoing industrialisation in the 19th century. The consequences were polluted air, rising rents and overfilled apartments with sanitation that was often disastrous. To tackle this issue, the British architectural theorist Ebenezer Howard developed the "garden city" concept. This aimed to solve the physical and psychological problems of city dwellers and industrial workers by taking a new approach to urban planning. Self-sufficient garden cities were to be created in the green surrounds of the large cities, connected to the latter by public transport. This plan included models for both non-profit financing and an urban structure that supported decentralised small businesses and industries.

Throughout Europe, reform-oriented architectural circles adopted these ideas, developing and adapting them to suit local conditions. The goal was to organise a life near the big city that was close to nature, and on land managed for the common good. In Falkenberg Garden City, the DGG’s pragmatic members realised some of these ideas starting in 1913. However, only a fraction of building projects were completed, as the First World War interrupted the work in Falkenberg. At that time the building site, which today is part of the district Treptow-Köpenick, still lay outside the city limits. However, with the amalgamation of urban and rural communities into Greater Berlin in 1920, Falkenberg was absorbed by the metropolis. Other prominent towns based on the garden city idea are Dresden-Hellerau and Essen-Margarethenhöhe.

Design

The blueprint for Falkenberg Garden City originally envisaged 1,500 apartments in various forms of row and detached houses. By specifying individual house types, residents kept planning and construction costs down. Many floor plans and dimensions could be used multiple times. Architect Bruno Taut, who was at the start of his career, was in charge of building planning. Why experts regard him as the "master of colourful construction" is easy to understand when you view this estate. Instead of using the expensive stucco, ornaments and building sculptures that were customary of the time, Taut designed the facades cost-effectively and employed stark colours. Different types of houses were combined visually into pairs or small groups by details of colour, facade, building shape and garden plantings. This lent the complex a very distinct appearance and inspired the sobriquet "Paintbox Estate". Even though similar garden cities sprang up across Europe, Falkenberg’s creative variety of colours and forms was unique but far from arbitrary. Not just the buildings, but also the green spaces received special attention. Falkenberg was the first residential estate for which a landscape architect was commissioned. The task fell to Ludwig Lesser, who had already made a name for himself in Berlin with his social commitment, public communication of garden design themes and large-scale planning. The private gardens, some of which measure up to 600 square metres (6,458 square feet), are located partly behind and partly in front of the houses. The gardens served as a design tool to loosen up the estate structure and gave residents the chance to grow fruit and vegetables. The use of climbing plants, espalier fruit trees, hedges and rows of trees set further accents and helped give the area a sense of structure. The acacia courtyard, where the trees occupy a space similar to a village square, acted as the hub of the first construction phase. The second section to be completed was along a street to the west called Gartenstadtweg, which rises towards the hill of Falkenberg.

Contemporary new buildings, some of which are part of the Falkenberg New Garden City project, are attached both at the upper and lower ends of the street. They are not included in the actual World Heritage Site, but form part of the organisation’s buffer zone and are therefore subject to stricter building regulations.

History

In 1910, a number of practically-minded members of the German Garden City Society DGG founded the non-profit Building Cooperative of Greater Berlin. Some of the key founding members were Adolf Otto, Robert Tautz and the brothers Paul and Bernhard Kampffmeyer. These like-minded individuals were trade unionists, Social Democrats and key figures in the life reform movement. They sought to develop Ebenezer Howard’s abstract ideas of a garden city into a building project for middle and low earners. To this end, they first founded a cooperative to organise joint financing of the project. After a two-year search, the cooperative acquired a plot of land – the Falkenberg estate near Grünau, which at that time was still outside Berlin’s city limits. Right away, there was great buying interest for the new housing estate. Whoever was accepted could invest in the building cooperative as members, thus helping to finance the construction of the estate. These individuals acquired co-determination and residential rights. Much of the building capital was approved under a law to promote non-profit housing construction, where the state provided one-third of the required funds in loans. In return, some homes were allotted to civil servants. Bruno Taut and landscape architect Ludwig Lesser came on board as planners. The large-scale designs were to create living space for about 7,500 people. Upon the outbreak of the First World War, however, all construction stopped, so that only 128 residential units instead of the 1,500 originally planned were ever built. The first modernizations took place in the 1960s and 80s. In the early 1990s, all exterior colours were meticuously restored, and in the early 2000s, a competition was held for concept called “Falkenberg New Garden City”. This experimental project was to be located close to the listed Falkenberg complex, contemporary in style but based on the original garden city concept.

Social issues

You had to take a conscious decision to join the Falkenberg cooperative and live in a community outside Berlin’s city centre. One can guess that the first residents were relatively similar in their basic political and social attitudes. This is hardly surprising, since the whole project went back to the spirit of the reform movement, probably appealing to a like-minded segment of the population. According to a 1950s brochure, 85 of the first 135 garden city families were readers of the Social-Democrat-oriented newspaper Vorwärts. In the early days of the Weimar Republic, Falkenberg’s “comrades” (members of a cooperative) were actively involved in the founding of workers' and soldiers' councils, and joined political actions such as the one against the Kapp Putsch (1920). Many residents grew their own fruit and vegetables in the gardens and enjoyed lively discussions and bartering. As some residents later recollected, small animals were kept in some gardens, and laundry could be washed collectively.

To meet the cooperative's goal of being open to all social classes, the mix of residents was designed to be diverse. Among the first were skilled workers, railway and justice officials, members of student councils, poets from Friedrichshagen and a widow with five children. This diversity did not hurt cohesion, and the sense of community and cultural vitality was particularly evident at Falkenberg’s summer festivals, which were held regularly from 1914 to around 1934. They were planned and organized by the community and by the 1920s, took on an increasingly avant-garde bent. That was due, among other things, to Falkenberg’s close ties with Berlin’s Volksbühne theatre, which had quite a progressive reputation. Partygoers from all over Berlin attended its festive parades, drama performances and other events. Whoever happened not to be acting or singing managed the theatre box office or got involved in some other way. This brought the community together, as did the traditional rite of eating blueberry cake hands-free and singing the Falkenberg Song. This tune was part of the local festival culture, regardless of whatever theme the summer festival had, and was penned by Albert Odrich, an estate resident. Over the years the song grew in importance and became a kind of community anthem. There was also an estate magazine called Der Falkenberg.

Places worth seeing

Further information

Quiz Questions

- Who developed the garden city model?

- Where did the German Garden City Society meet?

- When did Falkenberg become part of Berlin?

- What nickname was given to the estate?

- Who took care of the gardens and open spaces?

- Who designed Adolf Otto’s house?

- For how many people was Falkenberg originally planned?

- How did they eat blueberry cake?

- Where is the 3D model of the estate?

- What is the backstory of the "new garden city"?

Links and Resources (selection)

- Registered as Ensemble-Monument

- Registered as Garden-Monument

- Registered in Wikipedia

- Landesdenkmalamt Berlin (Ed.): Berlin Modernist Housing Estates / Siedlungen der Berliner Moderne, Berlin 2009 (D/E)

- Jörg Haspel / Annemarie Jaeggi (Ed.), Markus Jager (Author): Berlin Modernism Housing Estates, , Berlin 2007 (D/E)

- Landesdenkmalamt Berlin (Ed.), Sigrid Hoff (Author): Berlin World Cultural Heritage. Beiträge zur Denkmalpflege in Berlin, Bd. 37, Berlin 2011 (D/E)

- Deutscher Werkbund (Ed.), Winfried Brenne (Author): Bruno Taut – Master of colourful architecture in Berlin, Berlin 2008

- Landesdenkmalamt Berlin (Hrsg.), Sigrid Hoff (Autorin): Berlin World Cultural Heritage, Berlin Weltkulturerbe. Beiträge zur Denkmalpflege in Berlin, Bd. 37, Berlin 2011 (D/E)

- Stadtwandel Verlag (Ed.), Lars Klaaßen (Author): World Heritage Sites Gartenstadt Falkenberg / Schillerpark-Siedlung Berlin, Die neuen Architekturführer Nr. 166, Berlin 2011 (D/E)

- Deutscher Werkbund (Hrsg.), Winfried Brenne (Autor): Bruno Taut – Master of colourful building, Berlin 2008

- Kurt Junghanns: Bruno Taut 1880-1938. Architektur und sozialer Gedanke, Leipzig 1998

- Katrin Lesser: Gartenstadt Falkenberg. Gartendenkmalpflegerisches Gutachten, Archivrecherche, Bestandsaufnahme und Konzeptentwicklung, Berlin 2001–2003

- Harald Bodenschatz, Klaus Brake (Hrsg.): 100 Jahre Groß-Berlin, Bd. 1 – Wohnungsfrage und Stadtentwicklung, Berlin 2017

- Michael Bienert / Elke Linda Buchholz: Die Zwanziger Jahre in Berlin. Ein Wegweiser durch die Stadt, Berlin 2015

- Ben Buschfeld: Bruno Tauts Hufeisensiedlung – and the UNESCO World Heritage Site "Berlin Modernism Housing Estates", Berlin 2015 (D/E)

Please note: Resources in italics are only available in German.