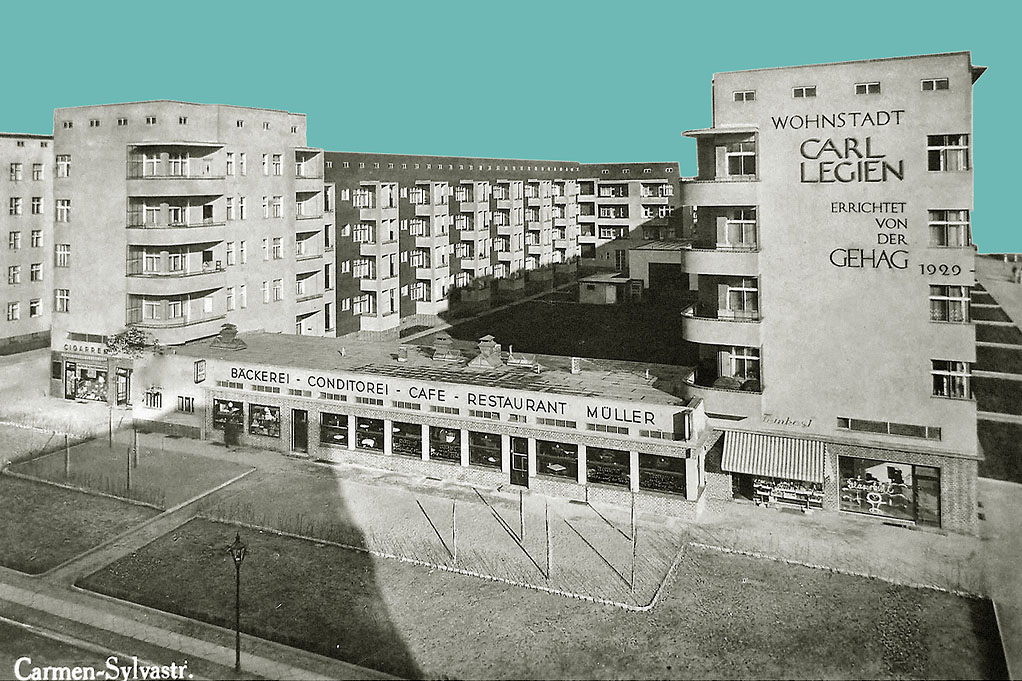

Carl Legien Housing Estate (1929–30)

Urban Living

Facts

- Location: District of Pankow, locality Prenzlauer Berg

- Public transport: S-Bhf Prenzlauer Allee

- Streets: Erich-Weinert-Strasse, Georg-Blank-Strasse, Gubitzstrasse, Küselstrasse, Lindenhoekweg, Sodtkestrasse, Sültstrasse, Trachtenbrodtstrasse

- Total area of world heritage: 8,4 hectares

- Total area of additional buffer zone: 25.5 hectares

- Number of flats: 1149

- Flat sizes: 1-1/2 to 4-1/2 rooms (80% thereof with a maximum 2 rooms excluding kitchen and bathroom)

- Constructed: 1928 to 1930

- Project manager: Martin Wagner

- Urban design: Bruno Taut

- Architects: Bruno Taut, Franz Hillinger

- Landscape architects: Unknown, presumably Bruno Taut

- Developer: GEHAG (Gemeinnützige Heimstätten-, Spar- und Bau-AG)

- Owner: Deutsche Wohnen SE (since 2021 part of Vonovia SE)

- Tenants, ca.: 1200

- Monument category: Ensemble-Monument

Message

The 1920s were a time of radical social and economic upheaval. The economy entered a stronger phase around 1925 (ushering in the "Golden Twenties"), but building costs soon had to be slashed after the global economic crash of 1929. This was particularly true of the Carl Legien estate, because of all six World Heritage Sites in Berlin, it is the most central and its property was expensive. Although not particularly large, the new apartments were well-equipped compared to the adjacent tenement blocks from Germany’s imperial era. The units at Carl Legien complied with the quality standards laid down in 1924 for reformed housing construction, and each dwelling had a separate kitchen, a private bathroom, and a balcony or loggia with an alluring view of the surrounding greenery. Bruno Taut had already tested U-shaped green spaces at the Schillerpark Estate and in the latter construction phases of the Horseshoe Estate. Here in Prenzlauer Berg, Taut geared his plans to the number of floors and the street layout specified by Prussian building regulations, which allowed up to five storeys. This way, the architect was soon able to prove that his urban planning concept worked in densely populated developments.

Design

The complex is located on both sides of Erich-Weinert-Strasse. From there you can look into six U-shaped residential courtyards, two of which are virtually mirror images of those across the street. Bruno Taut used a single colour scheme to identify them. Coming from Prenzlauer Allee to the west, you pass a turquoise-olive green section, then a sky blue and finally a light terracotta red. These main colours are in stark contrast to the green lawn and the balcony-like loggias painted in a pale beige-white. Some courtyards include small gardens for tenants, but these plots were only created after the war; in the long-term, they will be converted back into generally accessible green spaces. The real eye-catchers, however, are the somewhat higher five-storey buildings at the front, featuring corner windows and balconies that direct the view into the courtyards. The front doors are on the street side, their colourful windows and entrance areas set off by the monochrome facade. Anyone familiar with Bruno Taut’s other estates will recognize the architect’s signature in the colour contrasts, the door and window constructions, and the half-height top storey for drying clothes. Taut was backed by Franz Hillinger, head of the design department at the GEHAG housing association.

History

In the early 20th century lively Alexanderplatz, four kilometres south of the estate, was one of the busiest traffic junctions in Europe. Because this land in the city centre was relatively expensive, Taut and Hillinger had to accommodate as many apartments as possible in a limited space. Originally, three construction phases with around 1,700 residential units were planned, but in the end, only two phases with 1,149 units were completed. About 80 percent of them were one- to two-room apartments. Here, too, the goal was to build the apartments so cheaply that even simple workers could afford to pay the rent. Since reform housing had its roots in the trade union movement, the complex was named after Carl Legien, the chairman of the General German Trade Union Federation and an active member of the Social Democratic Party, or SPD. The estate is a prime example of how the names of streets and squares are often politically motivated. Carl Legien was one of the last complexes for which Martin Wagner, the city's building councillor, could draw on funds from the house interest tax until 1931, when an emergency ordinance cancelled state subsidies for residential construction. Starting in 1995, the typically vivid colours of the individual courtyards were refreshed as part of a long-overdue renovation of the facade. The giant lettering wrapped around the corner was restored for the 90th anniversary of the GEHAG housing association.

Social issues

Located in the district of Prenzlauer Berg, the Carl Legien Housing Estate is the fourth and most recent of the World Heritage Sites planned by Bruno Taut. Up to that point, Taut and housing association GEHAG had benefited from the extra residential demand fueled by the founding of Greater Berlin, and they built two- to three-storey estates in open-plan developments further outside the city centre. However, by 1929 this model was not financially viable in a location as central as Carl Legien. Space limitations in this Wohnstadt (“residential city”) are obvious in a comparison of population density. In Britz’s Horseshoe Estate, for instance, almost 2,000 residential units were built on 37 hectares (91 acres) of land, while the Carl Legien estate accommodated nearly 1,150 units on a mere eight-and-a-half hectares. Under these circumstances, it was not possible for tenants to plant their own gardens with fruit and vegetables, as was the case in Falkenberg Garden City. Even terraced houses were not economically feasible. But like the Schillerpark Estate, the residential complex Carl Legien clearly adhered to the slogan "light, air and sun" of the reform housing movement. All living space was oriented towards the green courtyards, and during the summer months, the open balcony-like loggias served as additional rooms. A special highlight were the wall cupboards, embedded in the sides of the loggias to store food. In the kitchen there was a sink and a gas stove, known at the time as a "cooking machine". To improve hygienic conditions, half-height washhouses for the residents were installed in two courtyards.

Places worth seeing

Further information

Quiz questions

- How were colours used?

- Why did they build more than three stories?

- Who provided the names?

- What was the quarter nicknamed during the Nazi period?

- What are the special features of the loggias?

- Where did you do your laundry?

- How big is the lettering on the corner of Gubitzstrasse?

- Where can you get a good coffee here?

- What do you see on the way to Greifswalder Strasse?

Links and Resources (selection)

- Registration as Ensemble-Monument

- Registration in Wikipedia

- Landesdenkmalamt Berlin (Hrsg.): Berlin Modernism Housing Estates, Siedlungen der Berliner Moderne, Eintragung in die Welterbeliste der UNESCO, Berlin 2009 (D/E)

- Jörg Haspel / Annemarie Jaeggi (Ed.), Markus Jager (Author): Berlin Modernist Housing Estates, Berlin 2007 (D/E)

- Landesdenkmalamt Berlin (Ed.), Sigrid Hoff (Author): Berlin World Cultural Heritage. Beiträge zur Denkmalpflege in Berlin, Bd. 37, Berlin 2011 (D/E)

- Stadtwandel Verlag (Hrsg.), Nicolaus Bernau (Autor): World heritage city, Welterbe Wohnstadt Carl Legien Berlin, Die neuen Architekturführer Nr. 184, Berlin 2013 (D/E)

- Deutscher Werkbund (Ed.), Winfried Brenne (Author): Bruno Taut – Master of colourful architecture in Berlin, Berlin 2008 (D/E)

- Kurt Junghanns: Bruno Taut 1880-1938. Architektur und sozialer Gedanke, Leipzig 1998

- Wolfgang Schäche (Hrsg.): 75 Jahre GEHAG 1924–1999, Berlin 1999

- Harald Bodenschatz, Klaus Brake (Hrsg.): 100 Jahre Groß-Berlin, Bd. 1 – Wohnungsfrage und Stadtentwicklung, Berlin 2017

- Michael Bienert / Elke Linda Buchholz: Die Zwanziger Jahre in Berlin. Ein Wegweiser durch die Stadt, Berlin 2015

- Ben Buschfeld: Bruno Tauts Hufeisensiedlung – and the UNESCO World Heritage Site "Siedlungen der Berliner Moderne", Berlin 2015 (D/E)

Please note: Resources in italics are only available in German.